I mentioned in a previous post that The Fall Guy was, at the time, this year’s movie to beat, whereas Challengers was, at the time, this year’s film to beat.

Now, mind you, I haven’t always been particularly lucky with new releases coming to my local cinema. So while I may have since missed out on features that have surpassed one or both (i.e. Kinds of Kindness, for all I know), my sentiment on Challengers still stands.

Indeed, the fact of its technical achievement alone makes Challengers worthy of all the praise its gotten, but director Luca Guadagnino’s latest goes above and beyond with its storytelling as well. The crisp, non-linear drama of it all houses a tale of love and masculinity that takes great joy in challenging (eh? eh?) our perceptions of relationships; it’s at once a mature and modern queer classic.

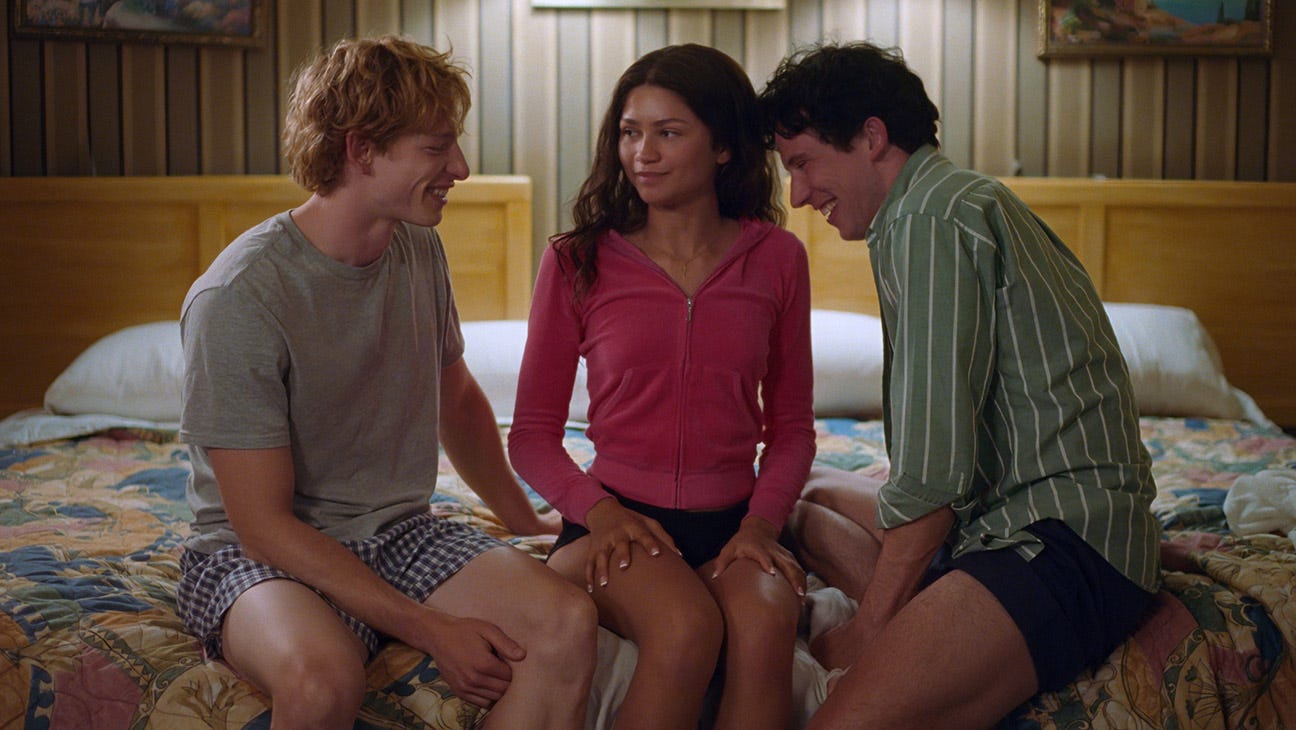

The film stars Zendaya, Mike Faist, and Josh O’Connor as Tashi Duncan, Art Donaldson, and Patrick Zweig, respectively. Tashi is a former tennis prodigy whose career stopped before it could take off after a fateful knee injury. Art is a professional tennis champion who’s looking to retire soon. Patrick is a down-on-his-luck tennis player who lives off of prize money at various tennis challengers. The x-factor? Art and Patrick were best friends since they were 12 (they’ve since become deathly estranged), they met Tashi when they were all 17, they both instantly fell for her, Patrick is now her ex-boyfriend, and she’s now married to, serves as the coach for, and has a child with Art. The three reconnect at a Challenger Tourney, and the battle begins.

To say that Zendaya, Faist, and O’Connor are a laceratingly sexy trio feels like beating a dead horse with a tennis racket; Zendaya’s imposing as the venomous Tashi, O’Connor serves a fascinating blend of wisdom and douchebaggery as Patrick, and Faist’s Art constantly looks like a lion is trying to tear itself out of his chest; a feeling he ping-pongs between accepting and resisting, and one he evokes with great mirth and equal devastation. Together, the three of them are pure magic.

But they aren’t the only top-class trio in play here; between Guadagnino, Trent Reznor, and Atticus Ross, Challengers has one of the sturdiest possible cases as a frontrunner for Best Director and Best Original Score. Indeed, the Italian gaffer—together with his cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom—presents Challengers in exuberantly dynamic fashion, constantly finding the peak of cinematic potential in the space of a tennis court, and brilliantly replicating it elsewhere (although, in many ways, the plot never leaves the tennis court; if you know, you know).

It boasts an almost symbiotic relationship with the Reznor-Ross score, comprised partly of breakneck synths and beats that elevate the film’s many blood-pumping, psychological cage matches, and partly of daunting melodies that communicate just the right amount of inner despair; pervasive, but conquerable.

Together, it creates an evocative package that makes one feel like they’re standing on the edge of the bodily plane, with all the mental and sexual stimulation that such a position would provide.

But let’s talk about Justin Kuritzkes’ script for a moment; a script that should happily stand alongside its artistic brethren as a frontrunner for Best Original Screenplay. The manner in which the scribe has rendered the concept of love here is the stuff of dreams; it’s utterly queer in its desolation of heteronormativity, which Challengers understands is far different from heterosexuality.

What do I mean by that? Tashi, Art, and Patrick are all straight characters, but Art and Patrick love each other, and it’s beautiful; the giddiness with which they take to their friendship is profoundly enriching to witness. That is love, but as straight men, they’ve been taught to want the same degree of love they have for each other, with a woman; enter Tashi, who both men see as that woman.

But Tashi? Tashi couldn’t care less about love even if she tried, and would in fact take great offense at the suggestion of trying, perhaps to the point of slapping the suggester. No, Tashi cares about tennis; playing and watching is her romantic and sexual pinnacle. So when both men become desperate for her number? She tells them that whoever beats the other in their upcoming tennis match gets her number, because that’s going to give her what she wants; a good tennis match.

But then along comes her injury, fracturing her relationship to tennis forever and leaving her unable to independently fulfill herself on it like she once did. All of a sudden, Art, the rising star, is her way back into the tennis world; Art loves Tashi, and Art’s place in the world of tennis makes him lucrative coaching material. Tashi gets what she wants, but Art finds out far too late that he won’t find the love in Tashi that he did in Patrick.

So now, Art is completely starved of love on account of Tashi being unable to give him that, and Patrick having also fallen out of his life after Tashi inadvertently drove a wedge between them. It’s no wonder he’s so depressed. Tashi, meanwhile, is also excruciatingly aware of her emotional limits, and she’s none too pleased about them.

Patrick, having long since contended with and accepted Tashi’s inability to love, then steps in as Challengers’ capital-P Protagonist, youthfully crude despite having entered his 30s. And yet, that proves to be his greatest asset as he endeavors to fall back in love with Art without leaving Tashi, his other love, in the dust as well.

And that’s why Challengers is such a fantastic queer film; queer love is defined by its ability to revolutionize how we relate to and care for and feel about one another. All of the misery suffered by Challengers’ characters has to do with their expectations of what they think love is supposed to look like, and all of their joy—authentic joy—has to do with their willingness to love in the ways that A.) they’re naturally and limitlessly capable of and B.) the people around them need to be loved. It’s an exhilarating and arresting finesse from Kuritzkes, and as if there wasn’t enough poetry in play here already, the next movie he’s writing is called “Queer.”

All-in-all, Challengers is an overwhelming case of game, set, match from all involved, with subtle intensities and intense subtleties abound, and a very good use of 131 minutes (or, if you’re me, 393 minutes).

At the time of writing, Challengers is available on VOD.