My decision to review The Darjeeling Limited was prompted by a few things. Firstly, I received the news that my local, notoriously vanilla cinema is going to be showing The Brutalist this weekend, which gave me the most powerful endorphin hit I’ve received all month. In that moment, I decided I would honor this lovely surprise by reviewing another Adrien Brody-led film; it was just a matter of which one.

This brings us to reason number two: I haven’t talked about Wes Anderson on this publication yet. I had been courting a review of Asteroid City for about a week, but neglected to pull the trigger for reasons I won’t disclose here.

Brody, of course, is a frequent collaborator of Anderson’s, and even appeared in Asteroid City, and so I can’t quite recall why I felt so compelled to pivot to The Darjeeling Limited specifically. Perhaps the thought of questioning such a thing was too frightening. I wonder what Wes Anderson would think of that.

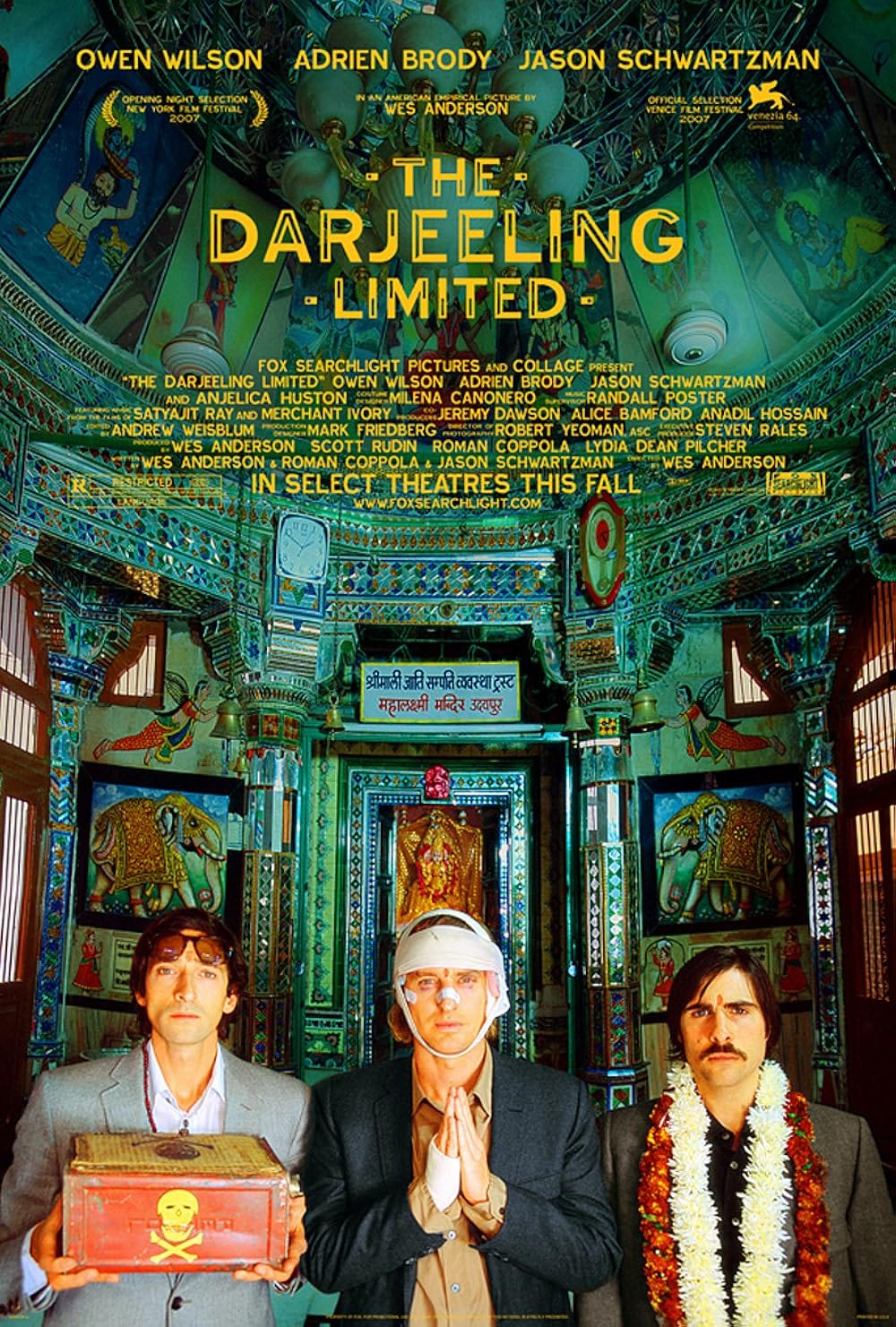

The Darjeeling Limited stars Brody, Owen Wilson, and Jason Schwartzman as Peter, Francis, and Jack Whitman, three estranged brothers with a dead father and AWOL mother who reunite in India for what Francis calls a “spiritual journey.” Boarding a luxury train — the eponymous Darjeeling Limited — the brothers share and withhold secrets, fall in love, and downplay the threat of a man-eating tiger.

I have complicated feelings about the word “auteur.” On the one hand, I think the notions of serial artistry that it captures are important tools in film criticism. But on the other hand, I believe that those notions should primarily exist independently; the idea of Anderson’s auteurship is much less interesting than that of Andersonian camerawork or Andersonian themes, for instance.

To that point, what I find most compelling about The Wes Anderson Movie™ is how it’s so often defined by a very challenging breed of humanism. These are movies that are stupendously blunt about their subject matter, and that subject matter is rarely light. And yet, they’re dressed and acted in such a way that divorces the emotion from the emotional truth while still maintaining the manifest of that truth (see: dialogue and deadpan performances).

This, very arguably, renders Anderson’s thematic musings too neat, tidy, and unceremonious to be truly cinematic. One might even use the word “impenetrable” to describe the human elements of these movies.

This, until you consider that Anderson creates human elements/truths that are meant to be entirely observable and functional, full of pizzazz yet unfriendly, sexless yet nutritious. Perhaps The Wes Anderson Movie™ challenges us to excavate its oppressively chiseled substance with our own, amorphously experiential humanity that a Lynch or a Herzog might instead invite us with.

Indeed, is there anything more human than wearing one’s unadulterated truth on one’s thoroughly unmistakable, Andersonian sleeve, only to see if we viewers deem such a truth as something worth bringing ourselves to?

With respect to this, why might so many of Anderson’s movies be titled after a location rather than any characters or events?

And of the Anderson films that aren’t titled after locations, how do they differ from the rest of his filmography?

In these ways, The Darjeeling Limited is quite safely one of the more quintessential pieces of the Wes Anderson mythos, and that can be most aptly understood in the context of the character Francis (Owen Wilson).

Francis, you see, is the ringleader of the brothers’ trip, and is the one who insists upon the three of them taking the aforementioned spiritual journey together. The goal, according to Francis, is to heal their familial wounds and perhaps settle other benign grievances that so often come with siblinghood.

The only problem? Francis is so determined to solve their issues with temples, peacock feathers, and prayers, that he neglects to try and solve them by actually speaking to his brothers about all of their problems. Jack and Peter are just as stubborn on this front (Jack, driven by the always-fun cocktail of avoidance and loneliness, Peter by guilt and pride), but I single out Francis because he’s usually the one to claim defeat in their shared quest to love each other, even if the logistics of that “failure” actually brings them closer together (the scene where the brothers haphazardly commence the peacock feather ritual is a key example of this).

Francis’ defining vice adds another unique element. He harbors a rather controlling nature; he insists on carrying his brothers’ passports, hides information about their trip that would have caused them to not come, and even takes his brothers’ orders at restaurants despite the fact that they’re sitting right there with him.

Thus, what might brotherly reconciliation even look like in Francis’ head? A world where Jack and Peter aren’t aggrieved by his behavior? Where they allow him to treat them this way? Does Francis really want to make peace with his brothers, or does he just want everyone else in the family to relieve all the pressure whilst waiving his own responsibility in that pressure’s creation?

But at the same time, is it fair of us to chalk up Francis’ behavior as nothing more than a vice? Is the ego not defined by our maladaptive tendencies that we’ve developed to feel safe/secure? Is Francis’ controlling nature not an off-shoot of that tendency in the same way that his sense of initiative is?

How might Francis’ natural tendencies balloon in the context of being the oldest child of three relatively neglected boys? Will his brothers still love him despite what his mortal essence insists upon? What if they don’t?

And this all ties back into the aforementioned “challenging humanism” that defines so much of Wes Anderson’s work. Love, healing, and all the rest of it is not a reward; it’s a choice we make, and it’s often made at least somewhat begrudgingly.

Indeed, just as we make the choice to bring ourselves to The Wes Anderson Movie™ despite the uncanny sheen it will throw at us, so too must the Whitman brothers make the choice to love each other through all of their bullshit, and perhaps show that love in ways that are unfamiliar (even scary) to them.

It’s all fine and dandy to easily unite together when faced with a common antagonist or point of peril, as the brothers so often do in this movie. The real challenge is uniting, both on the basis and in spite of, their interpersonal antagonism.

They know how to push each other’s buttons and they know what they need to talk about; they just don’t. Tell me you haven’t heard that song before.

Beautifully written. This is one of my favorites from Anderson, though perhaps some of that comes from being one of three brothers and dealing with some of the same issues. I think it's his artifice in production design and wardrobe that allows the straightforward emotions of his work to come out clearly in dialogue and staging, and that's why I keep coming back, even when the artifice is just too overwhelming (I was briefly not-very-enamored with The Grand Budapest Hotel, though I owe that a rewatch).

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com