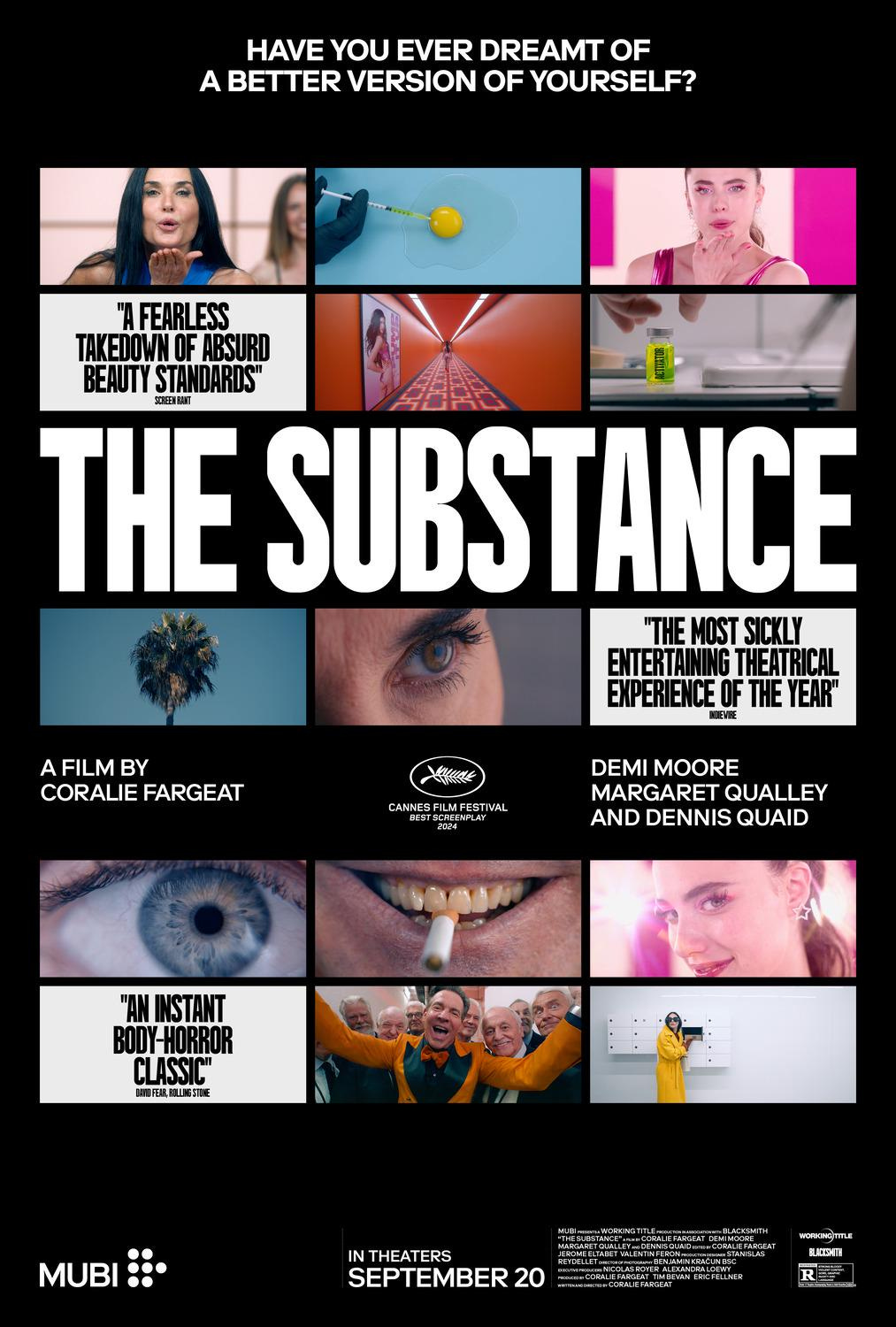

'The Substance' (2024)

I do not know how to explain to you why we need to expedite Coralie Fargeat's Oscar.

The Substance was a pleasant surprise in the sense that I didn’t think I would get to see it for quite some time. Around my neck of the woods, festival darlings and more demanding arthouse pictures are usually forsaken in the name of whatever the Minions are up to these days.

But somehow, someway, The Substance made it to my theater, and I saw it yesterday, and now I’m going to write about it because I think I have to.

What do I mean by that? I mean I see a lot of people talking about how it’s an insane, vomit-inducing laceration of beauty standards and show business and how we treat women in the media, but I see very few people talking about what it says about love, destruction, and the resulting war of attrition on the human spirit.

The Substance stars Demi Moore as Elisabeth Sparkle, the host of an aerobics television show that gets canceled on her 50th birthday, and no, that’s not a coincidence. As she watches the world leave her behind and she falls further into despair, she happens upon a black market drug known only as The Substance. The drug allows her to inhabit a much younger, much more physically attractive version of herself (who she names Sue and who’s played by Margaret Qualley), but only for a week, after which she must inhabit her original body for a week before going another week as Sue. The caveat? If she’s late to returning to her real body, there are irreversible consequences. Guess what happens next?

First, the essentials; Moore and Qualley are both brilliant, and the soundtrack is immaculate, but The Substance’s true power is in its visuals.

It’s exactly as evocative and visceral as everyone’s describing from both a body horror standpoint and simply a cinematic one, but what makes it all so exciting is the way writer-director Coralie Fargeat captures it all rather than what she captures. Her ability to tell a story and convey an idea or emotion using just the camera is completely and utterly sensational (pay close attention to the moment when Elisabeth is about to leave her apartment to go on a date, and pretty much every scene involving Dennis Quaid’s character Harvey).

The body horror elements will be divisive, and many will likely point to the film’s weak dialogue as a point of criticism, and perhaps to question what Cannes was thinking when they awarded Fargeat with the Best Screenplay award. Both of these things, however, combine for one, very intentional cog in this masterpiece. I’ll explain in a bit.

But first, understand that The Substance is, above everything else, interested in destruction; the destruction of ourselves for the sake of receiving adoration that is exclusively rooted in the entitlement of the adorer. This is not limited to media, nor is it limited to Hollywood stars; indeed, in the arena of evaluating people based on their bodies, we all have blood on not only our hands, but our entire bodies as well (particularly if that blood is sprayed en masse from an undeterminable orifice; yes, that’s symbolic).

Nobody loves Sue. At least, nobody loves Sue the person; they love Sue the product. As a thing to be desired. As a bloodless, sensual comfort. Pay close attention to how Qualley sells Sue as a character; she’s plastered on every billboard and television in town, and yet she’s not taking up any space whatsoever. She laughs and smiles along to everything, she paints a vague picture of a humble farm girl for her past (i.e. she’s implying she hasn’t internalized her stardom, meaning she’s sexually accessible on a mental/emotional level as well as a physical one), and she parrots the popular opinion about Elisabeth because it’s uncontroversial and allows her fans to be comfortable holding that opinion as they’re consuming Sue. She does not challenge; she barely even thinks. The whole package of Sue is rooted in the comfort of her beholders.

It’s no accident, then, that sleazeball Harvey’s defining characteristic is his intent to “give the people what they want,” because the people want comfort, regardless of how unhealthy those comforts are on a psychological and emotional level. The people don’t want to learn how to create value and love from within themselves, because that’s an uncomfortable process; they want to consume Sue the product, because her body offers a fantasy where someone that beautiful is a part of their life; better yet, the fantasy that she desires you, too. She gives you meaning because you can’t make any meaning of your own.

Similarly, Elisabeth/Sue doesn’t want to learn how to create value and love from within herself, because that’s an uncomfortable process (as we see during the weeks when the Sue body needs to rest and Elisabeth is forced to exist without the constant influx of attention and faux love. How does she do it? By consuming; an excess of food, overly-pleasant television shows, and other such comforts).

So instead, Elisabeth destroys her body so that Sue can happen more often, because Sue’s popularity offers a fantasy that all of these people love her. Those people give her meaning because she can’t make any meaning of her own. It’s a toxic relationship that goes both ways; a toxic comfort that’s predicated upon emotional (and, by extension, physical) neglect, mutilation, and destruction.

I’m going to offer a bit of a spoiler here next, so feel free to come back to this later if you want to go in completely blind. I maintain, however, that you’ll still be able to enjoy The Substance as a raw viewing experience even with this spoiler, and the scene in question is too important to not talk about here.

The best scene in the whole movie is when Elisabeth is inches away from terminating Sue, but spares her because Sue is the only source of love that Elisabeth has. After a quick blood transfusion, Sue comes back to life, looks at Elisabeth and the termination needle, and tries to kill Elisabeth. A desperate bid to survive? Mayhaps, but what does this scene think about how Elisabeth/Sue treats herself? The desperate, almost reverent care that Elisabeth puts into making sure Sue—in all her aesthetic pleasantness and engineered fuckability—survives, juxtaposed with the rabid hatred with which Sue tries to kill Elisabeth, the side of her that’s actually her rather than the product she puts forward.

What might that say about why and how we forego our authenticity for the sake of attachment and connection, however soulless it is? Our vulnerability for plasticity? Do we think our authenticity is worth giving? How can we be sure we will be accepted?

Well, we can’t, that’s why we commodify ourselves to receive love that’s contingent on the giver’s comfort. Everybody wants to be loved and nobody wants to be uncomfortable, so we destroy the uncomfortable parts of ourselves so that people will love us (at least, however much of us remains), and we consume shiny, comfortable products and people (and thoughts!) because that’s easier than confronting our insecurities.

In fact, we’re so obsessed with being comfortable, that many will evaluate The Substance by how uncomfortable it made them, and negatively so. They’ll be furthermore so repulsed by all the grotesque body horror, that they’ll completely ignore the film’s raison d’etre that the characters smack us in the face with using all the subtly of a tuba-fitted nuclear bomb (“I hate myself,” “You are one,” “You are the matrix (i.e. you create your reality),” “What is done cannot be undone”), and then have the gall to chalk it up as a shallow, shock-for-the-sake-of-shock commentary on Hollywood beauty standards, or, worse yet, just a really gross movie. All because they refused to engage with the movie on its terms. Refused to evaluate it by what it actually is rather than how it made them feel.

Refused to show love to the film’s true self because it’s too uncomfortable to look at.

Yes, this was calculated.

The Substance isn’t about beauty standards; it’s about our spineless entitlement to consumptive comfort — whether you’re the consumer or that which is being consumed — and how it’s destroying the human spirit.

So where do we draw the line? The more we drown ourselves in comfort, the more sensitive we are to discomfort. What happens when we do, inevitably, have to confront our imperfections, both physically and emotionally? Are we even capable of it?

At what point do we, as a species, reach a commodification singularity wherein we’re reduced to test-tube reproduction because the idea of sex has completely gouged our ability to stomach the act of sex? Pay close attention to the first, full-body onceover of Margaret Qualley’s body, and what the camera does when it’s about to show her unshaven vulva in the frame.

When might we whip out camps for the theoretically unfuckable, because how dare they be unfuckable in my presence? Make sure you’re more fuckable than the other girl, or kiss your humanity good-bye.

Ew, this movie has guts and organs in it, it has no value. Margaret Qualley is so hot. I want to die. Nobody gives a shit about me. I am fundamentally unworthy of love or even basic respect because my body isn’t like Margaret Qualley’s. I should be killed for it. I should kill myself. I am not the matrix. I am nothing. Consume me. Validate me. I exist to please you, and you exist to give me value. Happy motherfucking New Year.

Do you feel better? Are you comfortable now?

The Substance is now playing in theaters.

The question I wrestle with is: is this a different movie with an Ann Dowd instead of a Demi Moore? Which then invites the question: who gets famous from a workout show anymore? If that was supposed to be a metaphor, I confess I didn't understand it.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com

Your analysis of The Substance brilliantly connects its visceral body horror to the emotional devastation of self-commodification. The dynamic between Elisabeth and Sue reflects the tragic pursuit of external validation. By challenging our obsession with comfort, the film forces us to confront the destructive consequences of seeking shallow, conditional love.