I’ve written about Alien: Romulus once before on The Treatment1, back when I was still shedding what remaining, limiting beliefs I had about what film criticism ought to be and/or look like. It’s since become very clear to me that those were never my beliefs in the purest sense, nor were they anybody’s; they were investments in a safety net supplied by this modern criticism landscape.

What do I mean by that? Well, there’s nothing that I would call immediately marketable about my criticism, because my criticism — the actual, realized form of it — is not something that the market wants.

The market wants verdicts, not conversations. It wants publicity, not personal and collective growth. It wants to have its tastes validated, rather than cultivating that validation independently and standing on business — in tandem with other perspectives — about what it believes in.

Praising a Denzel Washington or Cate Blanchett performance is safe and easy. To actually try and say something objective or falsifiable about the performance is harder, and maybe you risk alienation by doing so.

The fact that objectivity is impossible is irrelevant. What matters is having the guts to believe that objectivity is possible, and building yourself out from there.

And what I believe in is humanity’s potential to heal their relationship with art, and therefore heal their relationship to themselves and each other. I believe films like Alien: Romulus are key to helping us do that.

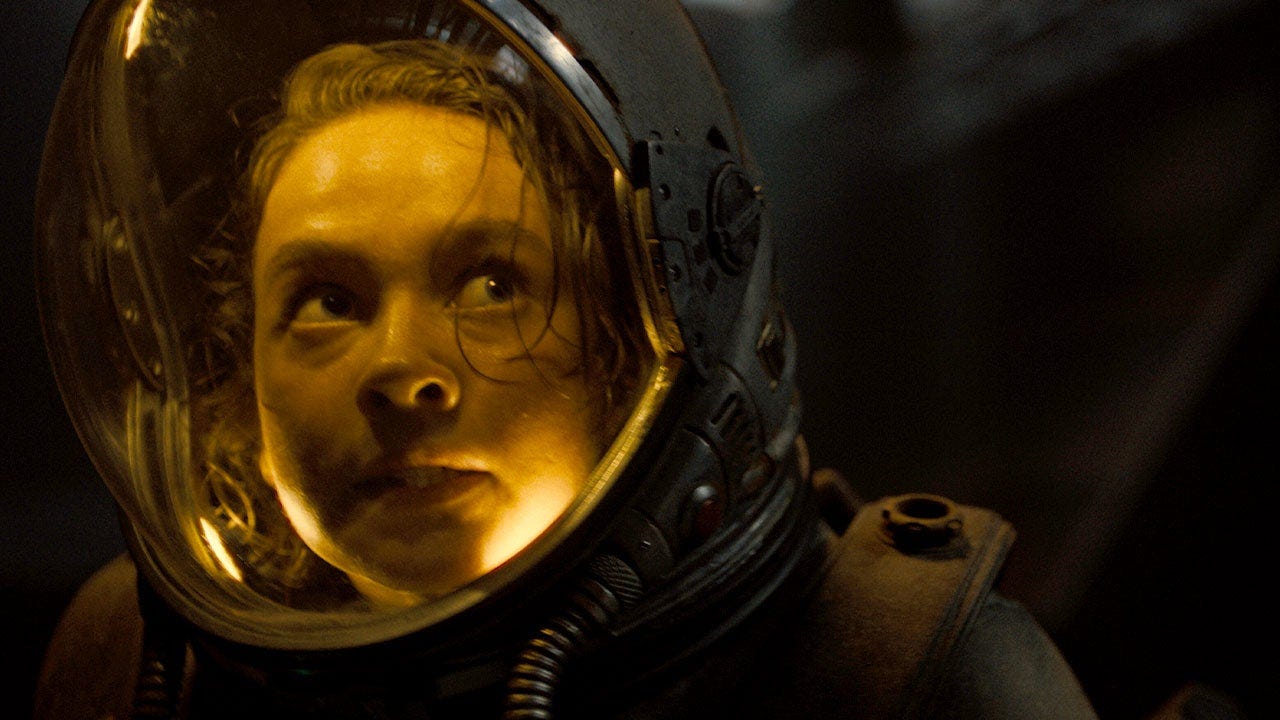

That statement sounds outrageous, I know. How can Alien: Romulus — that big-budget, canon-gratuitous, fan service-rich piece of major IP filmmaking that memorably toed an ethical line by using deepfake AI to make Rook look like the late Ian Holm of Alien fame — possibly be on the side of a brighter filmmaking future?

Two reasons. The first is that Alien: Romulus plays host to some razor sharp ideas about liberation — ideas that you won’t find in your run-of-the-mill cattle on the IP farm — that make it artistically valuable, and also pertinent to the conversation of said brighter future.

The second is that pop culture is a necessary tool for introducing (and perhaps reintroducing) these notes of artistic value to wider audiences.

You will reach fewer people with an essay on Pedro Almodóvar’s Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown than you will with an essay on Terminator.

But if you enable audiences to take pride in intellectually appreciating something like Terminator — which bridges the gap between nebulous, fandom-powered appreciation and appreciation for genuinely great filmmaking — there is now a firmer basis for intellectually appreciating films that don’t have Terminator’s fandom appeal. Like, say, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.

Hardly an airtight pipeline, but it’s something.

To that first reason, Alien: Romulus is, plot-wise, a film about liberation. Rain (Cailee Spaeny) and the remaining Jackson’s Star Five2 are living in a grotesque dystopia that grinds the life out of their bodies while dangling a forever-unfulfilled promise of freedom in front of their faces; a nauseating system that most viewers will have no trouble drawing an obvious real-life parallel with.

They of course want to fly away from this hellhole, and so when an opportunity comes to pillage a nearby space station for resources so as to make the nine-year flight to their nirvana of Yvaga III, they take it.

That’s all I need to say about the literal core, so let’s talk about the much richer subtextual core, wherein Alien: Romulus makes clear the price and discipline that such liberation requires.

Because when you escape a dystopian society like these characters do, you escape the dystopia, but you also escape the society. Without that fabric, even the smallest freedoms and blithest leisures we take for granted can no longer be indulged the way they once were. This is why Alien: Romulus’ characters are strategically underwritten — we aren’t meant to extrapolate any arcs, but instead the many ways this now-fatal lack of discipline can manifest and jeopardize that newfound freedom.

The most transparent case is that of Bjorn (Spike Fearn). He’s aggressive, impulsive, and cannot keep his emotions — particularly his bigoted anger towards Andy (David Jonsson) on account of an android that sacrificed Bjorn’s mother to save 12 other humans — under control.

In the context of ground-up community/society building, Bjorn’s antagonism and prejudice is now a pillar rather than the grating irritant it once was. That’s dangerous.

Then there’s the matter of Kay (Isabela Merced), who’s pregnant with the child of “some asshole,” and intends on bringing said child into a world that she and the rest of the teens have not even reached, let alone stabilized.

In this specific context, Kay’s pregnancy creates an significant strain on what could very well be sparse resources on Yvaga III — resources that she would also be limited in assisting with on account of said pregnancy. Having a bit of fun with “some asshole” is all good and fine, but the associated risks here become too great when you’re trying to cultivate something as precarious as independent freedom. Hospitals? Medicine? Shelter? Nutrients? Not easy to come by when you leave society behind.3

Tyler (Archie Renaux), meanwhile, styles himself as a sort of leader who feels personally responsible for the whole group — he does, after all, hatch the whole plan. At a glance, this is conducive to disciplined liberation, but pay attention to how this contrasts with Rain, who by no accident is Alien: Romulus’ protagonist.

Tyler takes full responsibility for mishaps and gives orders to the others, thereby indirectly discrediting everyone else’s autonomy and potential for independent contribution. This, while allowing his emotions to dangerously cloud his judgement. Put all of that together, and you have a slippery slope on your hands.

Rain, on the other hand, is defined by how she enables the people around her to contribute to the task in the best way that they can (Andy being the prime example); a crucial trait to have when building a new society.

It’s true that Tyler enables Rain by showing her how to use the gun, but if we understand the xenomorphs (the intended gun targets) as a parable for the shackles they’re trying to break free of, then Tyler’s enabling actions are restricted to the burning of the old rather than the building of the new.

The film, meanwhile, is primarily focused on the discipline we need to be capable of building the new, so Tyler’s thematic characterization still works here.

Elsewhere, Navarro (Aileen Wu) being the first to die is one of the most interesting aspects of Alien: Romulus, as it can be read in two very different ways to the same thematic effect. Navarro has three defining characteristics; she’s a pilot, she’s fearful, and most importantly — as evidenced by her prayer to the talisman around her neck near the start of the film — she follows some sort of faith or religion.

So, Navarro literally (and therefore, perhaps, metaphorically) steers the ship, and represents some sort of code with which to approach life. Could we then interpret Navarro’s early death as a warning to guard whatever foundational moral code you use to build your new society, lest you descend into xenomorph-coded vices and fall apart at the seams?

You could, but if we remember the common denominator of discipline here, another angle emerges. What is religion, after all, but a crutch for those who cannot cultivate a faith of their own?4 A set of beliefs that are adopted out of fear (fear, again, being Navarro’s other defining trait, as evidenced by her frequent panicking and freezing up)?

Indeed, is the zenith of spiritual discipline not freedom from the need for religion? If you seek freedom but fear arbitrary sin, can you truly achieve freedom? Did Navarro die from a lack of faith in her own mortal essence?

And finally, there’s Andy, the most important character in the whole film. He’s unwaveringly protective of everyone (even Bjorn), he’s resourceful but passive, and he tells adorably cringey dad jokes. Once he receives a module upgrade from Rain, however, he becomes more stoic, erudite, and independent, and makes a lot of decisions that require a heavy emotional reconciliation that the others cannot come by. He is, without question, the reason that any survival occurred here.

With this “upgrade,” however, he also comes dangerously close to completing his new directive of finishing Weyland-Yutani’s mission, at — if need be — the expense of the group’s lives. He’s eventually reprogrammed back to his old self before the point of no return, at which point Andy’s inner journey finishes serving its thematic purpose.

What is that thematic purpose? Well, in the act of breaking free from something (social norms, a literal system that you live in, whatever), you’re going to have to do things that will make everyone uncomfortable, yourself included (such as keeping a door closed so that the xenomorph only kills one person instead of potentially killing four).

But, as you do what’s necessary to survive and thrive, you mustn’t forget why you sought this freedom in the first place; for the physical and emotional prosperity of yourself and those who are on this journey with you. Andy forgot about that when he received his new directive, but — as evidenced by the life-saving dad joke he cracked near the film’s end — he remembered when it counted.

Speaking of uncomfortable things, let’s talk about Rook and Ian Holm for a moment. Everyone hated this aspect of the film — a realization of one of the more chilling ethical nosedives with the advent of artificial intelligence. I hate it myself.

And yet, did I not just spend most of this piece talking about Alien: Romulus’ cutthroat attitude on the relationship between discomfort and freedom?

Am I saying that we need to be okay with AI having a place in the films of tomorrow? Certainly not.5 But is the discomfort we feel around Ian Holm’s likeness not even slightly parallel to the discomfort that so often comes with chasing freedom? If we can’t stomach the ethical misstep of Ian Holm’s reimagined likeness, how can we possibly think we can stomach the ethical/emotional missteps that will come escaping the only way of life we’ve known before rebirthing a whole new one?

Because the truth is, there are countless emotional, recreational, and moral privileges that we enjoy because of the systems we begrudgingly live in. We can fantasize about freedom — or about an ideal cinematic ecosystem — because we are not immediately cognizant of what it will cost to get there on an individual or collective level.

Are these dreams worth chasing? Sacrificing for? I certainly think so. Know so. Alien: Romulus thinks so, too. But we still need to take realistic stock of the sacrifices we’ll make for whatever progress is made towards that dream; a dream that we may not live to see, to paraphrase one Luthen Rael.6

For those of you who may not know, I lost my job last week, and that gutted my livelihood and immediate future in more ways than such a thing usually does. Three days later, I lost two subscribers here. I am, in many ways, feeling very unstable right now, and I wonder how much that has to do with my spiky writing being ostensibly incompatible with the criticism market.

The thing is, I do what I do precisely because I believe in a better world for film, and I believe film criticism needs to evolve so as to realize that world. As it stands, so much emphasis is placed on liking and disliking things, and not enough on the simple act of connection with film, regardless of what we may like or dislike. I staunchly believe that that needs to change.

I want to dispel the notion that film criticism is a glorified vehicle for recommendations and determining who is better than what. Because in cultivating newer, bolder relationships with art, the way we watch movies is exponentially more important than what we watch. That’s why I’m banging the Alien: Romulus drum right now — it’s frankly smarter to explore the art of movie-watching with a recognizable arm of pop culture than dive cold-turkey into Yasujirō Ozu and expect the market to keep up.

I don’t want my identity as a film critic to be defined by screening privileges, takes that instantly gratify the public, and a high follower count. I want to actualize meaningful dialogue, and I want to do it whilst being on the same playing field as everyone else. But if I have no platform, perhaps replete with those privileges and followers, how can I expect to change what I want to change?

Indeed, what if I need to play the market’s game in order to build the platform that can then give my actual criticism the wider resonance I seek?

Perhaps the demoralizing quest for market stability — and not stability itself — will prove to be the real sacrifice I make here.

Somewhat similarly, maybe artists need the platform of pop culture in order to reclaim the arts sector. The grossly unimaginative Rhys Frake-Waterfield — who birthed the Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey films alongside a whole shared universe of creatively dearth cashgrabs — is nevertheless walking proof of that claim. This hacky opportunist was given permission to masquerade as a filmmaker because he sold tickets, and he sold tickets because he leveraged the Winnie-the-Pooh IP. He’s utter poison to the landscape, but his method can be used for good.

Fede Álvarez’s work here is a fantastic example of nutritious IP storytelling, and the foremost duty of film critics is to mine it and articulate it so that the public can have a stronger relationship to art than they did yesterday. That’s why I, like so many other artists who share this dream with me, will not be going anywhere. There’s simply too much shit in this world that’s in need of fucking up, and — with respect to Alien: Romulus’s wisdom — maybe I need to fuck up my own shit in order fuck up all of that shit.

Indeed, who knows what will be born out of my newfound unemployment? I hope you’ll join me in finding out.

Whose most valuable portions have been carried over and reimagined here.

I’m not apologizing.

Not that these things are necessarily easy to come by in a society either, but there’s nevertheless potential for accessing them, which you fully relent upon leaving the society.

But even then, AI is not going to go away if we don’t disempower the system that enables it, and that will also require steps that we might not immediately be okay with.

Andor, of course, is another great example of using pop culture as a battering ram to a better world for visual storytelling.

The way you approach reviews is so refreshing and frankly necessary, and even if the market isn’t ready for reviews of media that delve deeper than a simple five star rating system, we need the relationship with art you demonstrate in your writing more than ever. I’m excited to follow your work wherever it leads ♥️

I'm sorry you're currently without employment. It's always occurred to me that film criticism was being phased out by the general public, lest it morphed into something new and unusual (I am, admittedly, trying this, though not in a commercial aspect). I hope there's a home for your unique insight. I know there is, I just think the right person needs to speak up and bring you onboard.

These are salient points about "Romulus". I do feel like modern studio filmmaking has completely abandoned the youth, and as such, "Romulus" feels like the one movie addressing the idea that, thanks to technology, more than previous generations, the young ones today seem determined to interrogate the rest of us and ask, why did you do these things and for what purpose? I hope this exploration continues in an inevitable sequel.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com