One time I saw someone characterize Samara Weaving as “Margot Robbie that men actually have a chance with.”

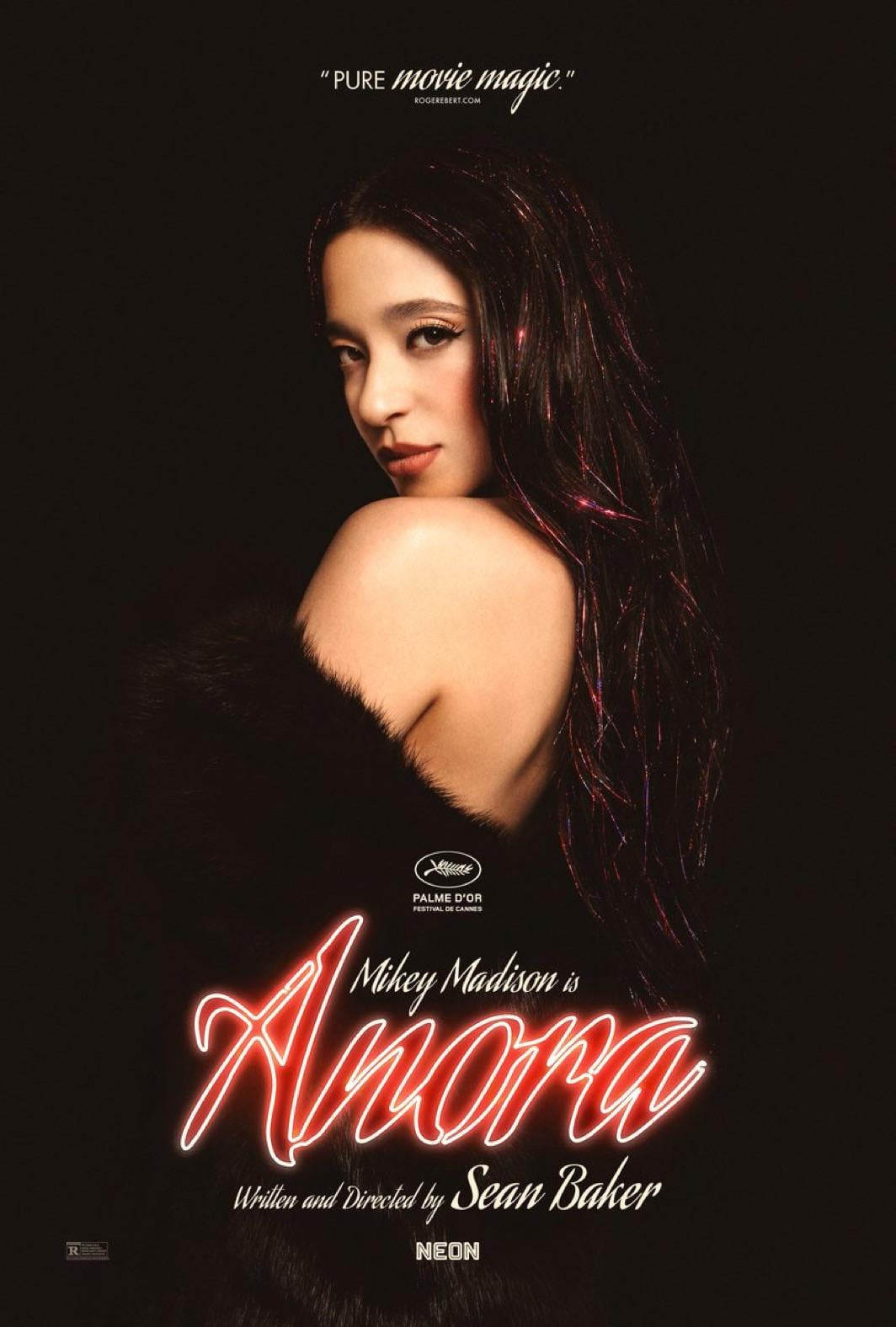

Anyway, today we’re talking about Anora.

Anora stars Mikey Madison as Anora “Ani” Mikheeva, a sex worker living in a Russian-American neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York. She’s introduced by her boss to Ivan “Vanya” Zakharov (Mark Eydelshteyn), the young son of a Russian oligarch who blows off college to play video games and party in his parents’ mansion. He repeatedly hires Ani over and over again, including a $15,000 payment to be his girlfriend for the week on a trip to Vegas, where he winds up proposing to her. She agrees against her better judgement and moves in with him, but their idyll(?) is shattered when Vanya’s family comes knocking and demand the marriage be annulled.

Anora is a supremely difficult film to talk about, and that’s mostly a testament to the brilliance of its emotional thrust, which itself acts as a sort of indictment of anti-emotion. A day could be made of dissecting its literal, subtextual, and technical proceedings, but for the sake of hitting that sweet brevity-to-nutrition ratio, we need to talk about Sean Baker’s humanism here; a humanism that understands how important it is to contextualize our subconscious quest for honest love in the regretful throes of impulse and misanthropy.

Ani is neither a good practitioner of nor familiar company to love. As a sex worker, it’s more or less necessary that she divorce emotional intimacy from sexual intimacy on a very conscious level, and the psychological impact of that can’t be downplayed. In any case, this is a place where she’s valued for her body and for how well she manages drunken egos. She must indulge and embody the fantasies of her clients, and the subsequent interactions merely masquerade as intimacy, with a touch of condescension to boot.

But when this faux-intimacy is taken out of the equation, we see that the aforementioned divorce of emotional intimacy follows Ani into her interpersonal life as well. Without an ego to manage, condescension balloons into snark and cheeky cynicism (either at the expense of the person she’s talking to, or a person she’s talking about), and because her environment values her body rather than her mind or soul, she probably doesn’t have a good relationship with her sense of purpose.

And when you don’t have purpose, you seek pleasure. Enter Vanya, a walking, talking, bottomless pit of hedonism that’s infatuated with Ani (or, more accurately, the pleasure that she provides). Ani’s used to the type of raw attention that Vanya showers upon her, but Vanya can provide her with much more exclusive pleasures; trips to Vegas, endless booze, mansion parties, and stacks of cash galore. All Ani needs to do is make him feel good.

Vanya, of course, foolishly assumes on account of his youth that the moment he so drunkenly, brazenly lives in is one that will last forever. Combine that with Ani’s warped interpretation of human connection, and you can see the downfall of this marriage coming from a mile away.

Because you know what isn’t pleasurable? Emotional intimacy and vulnerability, and Anora is an indictment of how we forsake these things in the pursuit of pleasure, or even simply how we omit them from equations that they absolutely should not be omitted from (like, say, marriages and families).

True, honest emotion is so alien to Ani, in fact, that when Igor (Yura Borisov’s muscular henchman character) is revealed to have kept Ani’s ring safe for her all this time, she doesn’t know how to respond other than by giving him a lap dance, followed by fucking him in the driver’s seat of his car.

The bursting into tears that follows is equal parts cathartic and devastating; cathartic because she finally allows her steely sheen to fall down and make space for her most vulnerable feelings, and devastating because she may have just realized how much she wants to love and be loved — really love and be loved — and how difficult it’s going to be to get to a place where she can do that sincerely.

This breakdown, in the arms of Igor, who she previously called a faggot-ass bitch because he insisted he wouldn’t have raped her if they had been alone at the mansion near the start of the film. Igor, who couldn’t hide his smile when Ani stood up to Vanya’s mother, who always made sure she had something to keep her warm, and who insisted to Vanya’s parents that Vanya owed Ani an apology.

Igor, you see, knows a thing or two about only being valued for one’s body, all while that body harbors a soul that rightfully pleads to valued for the fact of its value. Indeed, sex workers like Ani and bodyguards like Igor have survived in this world by buying into the idea that their bodies define their value, while the ultra-rich — in all their epicurean glucose — insert those people into their slush piles of indulgences and assets.

Is it not a profound tragedy that both ways of life here, both ends of the class privilege spectrum, are ostensibly defined by their rejection of humanity, and yet only one is deemed worthy of respect by the world we live in (and it’s not the sex worker)? Pay attention to the glee with which Vanya’s mother threatens to ruin Ani’s life, and how so many of these relationships are primarily defined by either power or commodification.

In this way, Anora neither completely champions bodily laborers nor takes complete aim at the ultra wealthy, but instead advocates for the human that resides in everyone, apologizing to it on behalf of the world that the body was brought up in.

There’s something esoterically gutting about having shared humanity be rooted in a somewhat-eager, somewhat-helpless abandon of that humanity, but what Anora does that’s so important (and why it’s almost certainly going to be ever-present on the internal Oscars podium at least) is that it doesn’t play this emotional tragedy as a fact of life, but as exactly what it is; an emotional tragedy.

Anora doesn’t aim to depress or despair, but to highlight how so much of the world’s vitriol and sarcasm is a survival tactic, and how even the most subtle, unceremonious act of compassion and love might be all somebody needs to come back into their humanity, if only for one, potentially lifechanging moment.

Samara Weaving has a more comedic flair that I find to be sweepingly adventurous all while a certain subtlety is maintained, and I find Margot Robbie’s is more a penchant for spunky flourish and soft power. Both are fantastic artists. I know neither of them personally.

All true, but in the end I felt a profoundly empty depression? This one didn't get me like it gets others, I don't know. Just seemed sour. I agree with your well-made points but maybe I just wanted more from this.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com