I went and saw Captain America: Brave New World for work purposes a couple of days ago1, and I almost got run over by a car on my way to the cinema.2 Not every woman can have it all, I guess.

The kicker? I didn’t even end up seeing Brave New World. I looked at it, certainly. More accurately, I looked at a screen that was displaying what we understand to be Brave New World, but I did not see anything. It is not possible to see this film, only look at it.

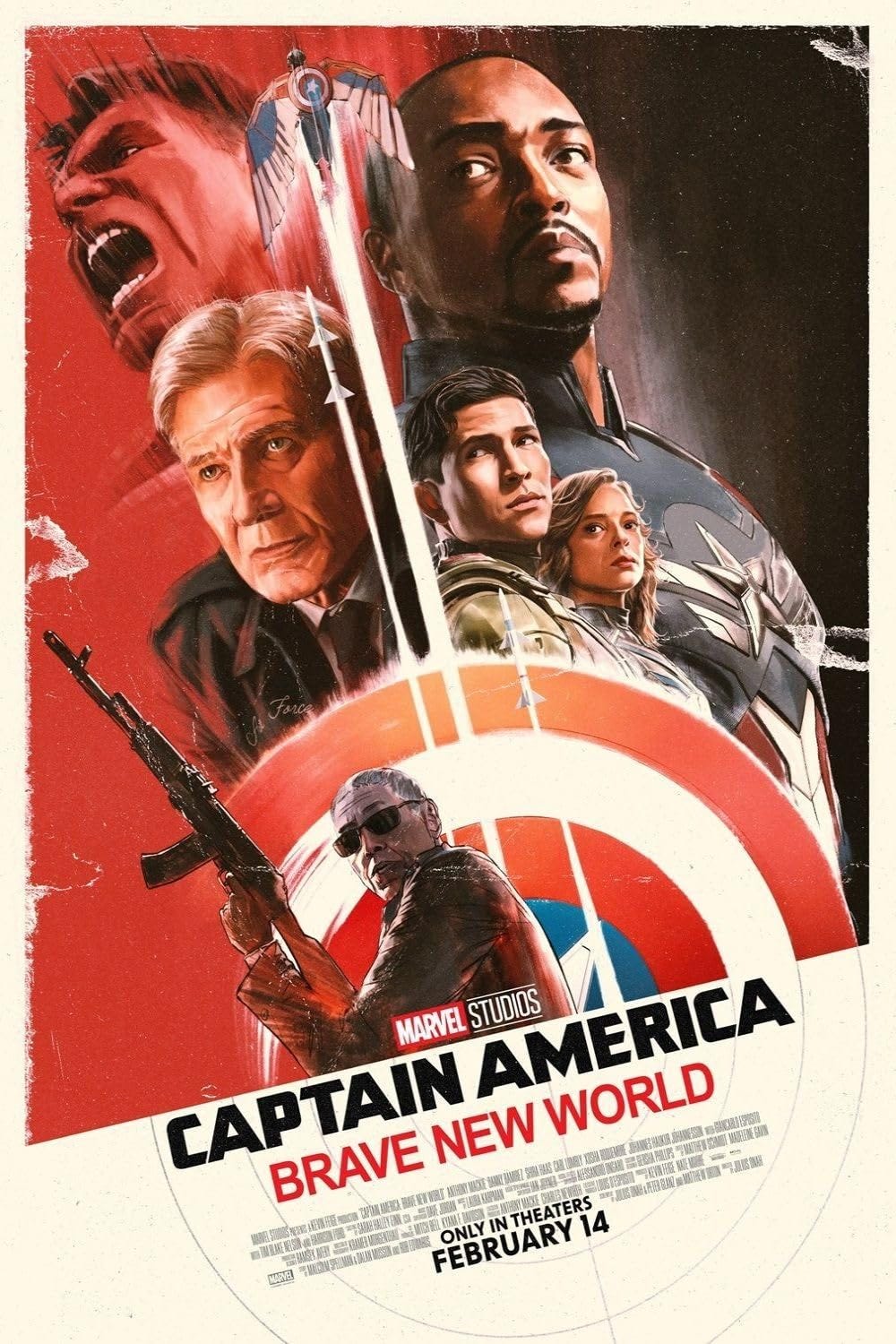

More on the look/see dichotomy in a minute, but this is the part where I tell you all that Brave New World is the worst movie Marvel has ever put out.3 It’s a hodgepodge of happenstance, hardly-coherent plotlines whose only tangible objective is to not say anything with its chest, lest it ruffle feathers or divert neurons. This, while heavily saturating itself with the sheen of Earth-199999 and all of its nuances — both familiar and revelatory — so as to distract from its nothingness.

In other words, Captain America: Brave New World is for the Fans.

Some of you may have noticed this about me, but I have never referred to myself as a Fan of anything, and I actively reject being described as such. I love Peter Jackson’s King Kong, but I am not a Fan of Peter Jackson’s King Kong, and that’s because loving something and being a Fan of something are two different things.

When you love something, you’re independently recognizing and admiring whatever expression that something puts out into the world. You don’t surrender to it, and you don’t claim it — you shake its hand.

When you’re a Fan of something, that admiration is no longer independent. You’re absorbing the something into your sense of self. As a Fan, you like this something because to not like it would be to compromise your identity. If the new Marvel is stupid, then you’re stupid. If your hockey team loses, you get laughed at.

This is the part where one of you says I’m being pedantic, and the part after that is me saying “Yes, that’s the point.” I’m perfectly aware that “Fan” is a word we throw around very casually, and that we don’t consciously associate it with something as tamely dystopian as defining ourselves with the brands and celebrities that happen to package our most fondly-regarded art.

But within the minutiae of separating “loving something” and “being a Fan of something,” we tap into an awareness of how we bring ourselves to things — and, just as importantly, how things bring themselves to us — that we maybe weren’t considering as seriously as before.

Which brings me back to Brave New World and the similarly-pedantic point of seeing versus looking. We can use this to further break down the nuances of loving something as opposed to being a Fan of something.4

To see is to take conscious ownership of your role in creating an understanding (new emotions, new ideas, etc.) with a subject, which is done by combining your own potential for expression with the expression offered by the subject. When you see, you value your expression and the subject’s expression as two separate things, and the endgoal is that new understanding between you two.5

You see something when you love it. Seeing is active and intimate. You (meaning your endless potential as an expression) matter in the act of seeing.

Conversely, to look is to allow yourself to be defined by the subject, which is done by disregarding your potential for interaction and expression, regardless of whether or not the subject offers an expression of its own. When you look, you’re relying on the subject to contextualize who you are, and you’ve decided that you exist so that the subject can exist, and vice versa. Not do, not be, not express; just exist.

This existence, this complacency, this validation, is the endgoal. Expression (and, by extension, interaction) becomes irrelevant because that implies welcoming new emotions or ideas, which goes against complacency.

You look at something when you’re a Fan of it. Looking is passive and shallow. Your body — not you, just your body — is the only thing that matters in the act of looking.

But, again, differentiating between looking and seeing isn’t what’s important. What’s important is the philosophy behind the act of making that differentiation.

We can demand something of ourselves and the subjects for the sake of growth (seeing, loving), or we can submit to whatever surrounds us — including the subjects — for the sake of complacency and avoiding change/conflict (looking, being a Fan).

Seeing is what happens when you happen to the world. Looking is what happens when you allow the world to happen to you.

Brave New World allows the world to happen to it, because Marvel’s goal is mass market appeal, and it’s easier to submit than it is to demand. This is true of the film as well the audience.

As a result, the film withholds self-expression so as to avoid friction with other expressions (meaning audience members). That lack of friction makes it easier for audiences to submit, but it’s at the cost of the film becoming impossible to well and truly interact with.

In other words, even if one wanted to see it, it can only be looked at — you can’t create a new understanding if the subject doesn’t give you anything (i.e. an expression) to build an understanding with. But Brave New World, beholden to Marvel’s mass market appeal goal, has no need to be seen so long as Fans exist — so long as Fans are looking.6

When the Fans exist, Marvel exists. When Marvel exists, the Fans exist. Existing is the floor for everyone, but in Marvel’s case —and therefore the Fans’ case — it’s also the ceiling.

Indeed, the only tool Marvel Studios needs is the Marvel Studios stamp of approval — so long as that exists, Black Panther and Quantumania are the same to Fans, as is Brave New World; another product to absorb into one’s Marvel-shaped personality.7

Worse yet, that stamp of approval takes precedence over any good an MCU film could do. Look at Spider-Man: No Way Home, whose most fascinating narrative asset is the inclusion of Tobey Maguire’s and Andrew Garfield’s Spider-Mans, not because of the nostalgia huff they provide, but how intriguing their presence is in the context of a Spider-Man story.

The mythology of Spider-Man is primarily defined by not only how much pressure he’s under, but his inability to speak about it with many people, and the inability of most to understand his pain anyway.

There’s no world in which Tom Holland’s Peter Parker bounces back from his despair without the support network of Maguire’s and Garfield’s Peter Parkers. They are the only ones who can well and truly empathize with his experience and enlighten him on the possibility of healing.

But all anyone seems to talk about is how No Way Home’s greatest victory was a planet-sized, nostalgia-heavy endorphin hit. This, occurring from looking(!) at all of these characters from legacy Marvel flicks (Andrew, Tobey, Willem Dafoe’s Green Goblin, Alfred Molina’s Doc Ock, what have you).

That’s because it’s not about appreciating what Marvel movies do, are, or can be — it’s about evaluating them solely by how well they serve the Fans and their personalities. The Fantastic Four: First Steps could completely revolutionize the way we think about celebrities and dysfunctional families, and the all the Fans would focus on is the sneaky digs at Josh Trank’s 2015 film.

Let people like what they like? Sure, but are those people really liking anything if those people don’t belong to themselves?

Because you don’t actually like Captain America: Brave New World; it just so happens that it’s a thing from the thing you’re a Fan of, and it goes down without incident. You leave the cinema as unchallenged as you were when you walked in. Perhaps — nay, almost certainly — even less challenged.

And believe me, I’m hardly in any position to make an enemy out of escapism, but that willful adherence to unmoderated comfort is the enemy of growth. Experience. Living. The reasons we’re on this planet.

It’s one thing to limit yourself, but why would you be okay with the limitation of something that you purportedly love? When we encourage the limitation of other human beings for the sake of our comfort, we call that narcissism, not love. If you truly loved Brave New World or anything that comes out of Marvel these days, would you not want it to be itself? To stand for itself? To nurture and then imprint its perspective on the storytelling and/or genre landscape? To have a perspective in the first place?

Of course you would. But you don’t, because you don’t love it. You’re a Fan.

Any offense taken from the problematization of the word “Fan” is derived from an attachment to that word and whatever you associate yourself with being a Fan of. My goal with this piece is not to call people out for liking things, but to help them take back whatever power that attachment has over them. Words have power. We have more.

And when you’re a Fan, your fav needn’t be the best version of itself — hell, they needn’t be any measurable version of themselves — so long as it serves you. Indeed, to paraphrase Tim Blake Nelson’s Leader, who’s really playing who in this Fans and brands equation?

I well and truly adore my job, and generally don’t mind swallowing bad media so long as I can offer up a response to it that’s conducive to our cultural climate. It was embarrassing, for instance, to walk — by myself — into the opening showtime of Harold and the Purple Crayon as a 27-year-old, but it gave me fuel to go to bat for children’s media, so I ultimately welcomed the whole ordeal.

I don’t know what specific bigotry this is, but Atlantic Canadian drivers are just not a demographic I can get behind (or in front of, judging by my grazed purse).

And please, save the parroted cynicism on franchise filmmaking and superhero films for just a second. It may be true that the best the MCU has to offer pales in comparison to, say, a middle-of-the-pack A24 release, but there have been plenty of solid-to-great stories out of this canon (Black Panther, Captain Marvel, Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, Captain America: The First Avenger, to name a few), while the genre as a whole has played host to such genuine juggernauts as 1994’s The Crow, Beau DeMayo’s X-Men ‘97, the Spider-Verse films, and M. Night’s Unbreakable. All of these, trafficking in emotional storytelling driven by character and supplemented by genre bells and whistles, with a dash of thematic heft as well. Brave New World could never sincerely be described this way.

Listening versus hearing is a good way to think about this, too.

If the subject was sentient (say, a lover), the same would be true on their end. In the context of a seer-to-film interaction, the seer’s response carries all of the significance because the film is a fixed expression that cannot consciously make use of the aforementioned new emotions or ideas that come from the interaction.

In other words, if digestibility is its North Star, then self-expression is not an economical route for Brave New World to take.

If this seems reductive, it’s because the word “Fan” is too normalized. I’m sure many self-identified Fans admire Black Panther and despise Quantumania while actively wanting Marvel movies to be genuinely good. Those people are not Marvel Fans; those are people that love Marvel movies (and, in all likelihood, movies in general). I am one of those people.

What I landed on a few years ago was how deeply disturbing the argument, "But it's my childhood!" is when so casually embedded in how we think of art and entertainment. First of all, do you WANT your childhood to be the legally enforced intellectual property of a liability-free media conglomerate? Secondly, don't you have enough pride in your own childhood to then demand the work live up to the original qualities that endeared you to the movie?

In short, "it's my childhood" does the exact opposite operation it should: reduces the judgment of the viewer while greases the saleability of bad work. If "your childhood" has any personal value, you would protect it with great judgment and little permissiveness.

Or, we can then all agree that your childhood was shitty, because you spent it watching movies instead of developing your own concept of self, personality, and character.

MY childhood was spent running around the mountains pretending I was lost in Jurassic Park, but Jurassic Park sure as shit was not my childhood and does not justify seeing a Jurassic World movie unless I hear indication that the movie is actually good on its own merits.

I think people get bogged down in how over-crowded these movies are -- with gratuitous violence and endless characters derived from the IP -- and they lose sight of what these elements ultimately crowd out, which is agency. Too many of these characters and storylines are reactive, and you wonder, reactive to what exactly?

Avengers: Endgame was ultimately damaging. People rooted for those heroes because they had a basic goal -- resurrect a bunch of dead heroes (these movies do NOT care about the average non-superhero human). But in doing so, they were defeating the last five years of Thanos' actions, which were to wipe half of life off the board.

The shows dabbled in this, but ultimately, we have no idea what happened in those five years with everyone gone. "The Falcon And The Winter Soldier" implied that those years were prosperous for some people, and the return of the rest of everyone would be damaging. This was a frustratingly inarticulate position, but more pointedly, Mackie's Captain was nonplussed by all this. He was stopping terrorism, but we never really see if he agrees or disagrees with this position. His fists suggest that he doesn't, but at the show's finale he spoke up against calling these people terrorists, suggesting the truth was more complex. If only he, and the show, made us privy to these truths. Instead, Cap seems to simply fight for the status quo, and not only is this socially regressive, but it's empty, since we don't even know what the status quo is.

More and more, these overplotted movies rob the lead characters of agency so we end up realizing we have no idea what these heroes want, what they're fighting for. I sat through "Brave New World" thinking, if Anthony Mackie goes home now, I assume some other Avenger will show up to clean up this mess, and no one will be the worse for wear. I kept wondering, given the racially-charged nature of his interactions with the President, and the incident involving Isaiah Bradley, if maybe he'd be fed up with this administration and go home, leave the shield behind. Or maybe he'd start packing heat again like he did in earlier movies and start dealing a very violent set of justice. Maybe he ignores the Avengers and dials up assistance from Jon Bernthal's Punisher. Wouldn't that be a statement?

Instead I'm left wondering, what does Cap want here? And, more pointedly, what does Anthony Mackie want here? Does he really want to be the Captain of America, without once acknowledging what America is or has become? When are these Captain America movies going to actually address America? People (myself included) have reached to see Trump or Biden or whomever in President Ross, simply because we want to grant a little bit of loaded real-life significance to this character and what he means. Because without that, this isn't about anything. President Ross at least wants things in this movie. What does Captain America want? What did Shang-Chi want? What do any of these guys want anymore?

I remain fascinated by this great Marvel experiment in 2025 because it asks us, as a society, what a hero actually does in the modern world (pointedly, specifically using characters created in the 1960's as far as the Falcon, President Ross and "The Leader"). More and more, it just seems to be, wait for someone to show up and get punched. Doesn't feel like heroism to me.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com