I wanted to hold off on this one until I actually got my hands on Novocaine’s screenplay (penned by Lars Jacobsen), but as of late, I find myself overflowing with a wholesome Filmstackian patriotism that I think prudent to utilize at this moment in time.

As such, this is the part where I tell you all that the reason I only post once a week is because I’ve had my nose to the screenwriting grindstone for the better part of three months now.1 Generally speaking, if I’m not on Substack, I’m in Beat.

This to say, I have no intention of letting the new film criticism be my only contribution to this cinematic future that we’re all pushing towards together. To not put my own stories on the table would be self-betrayal of the most grotesque caliber.

And screenplays, of course, are the lifeblood of any filmic body, and where NonDē interrogates and redefines that body, what I want to do here is interrogate and redefine attitudes about that lifeblood. I want to get a pulse on the world that I want my screenplays to grow up in.

And Novocaine is going to help me illustrate it.

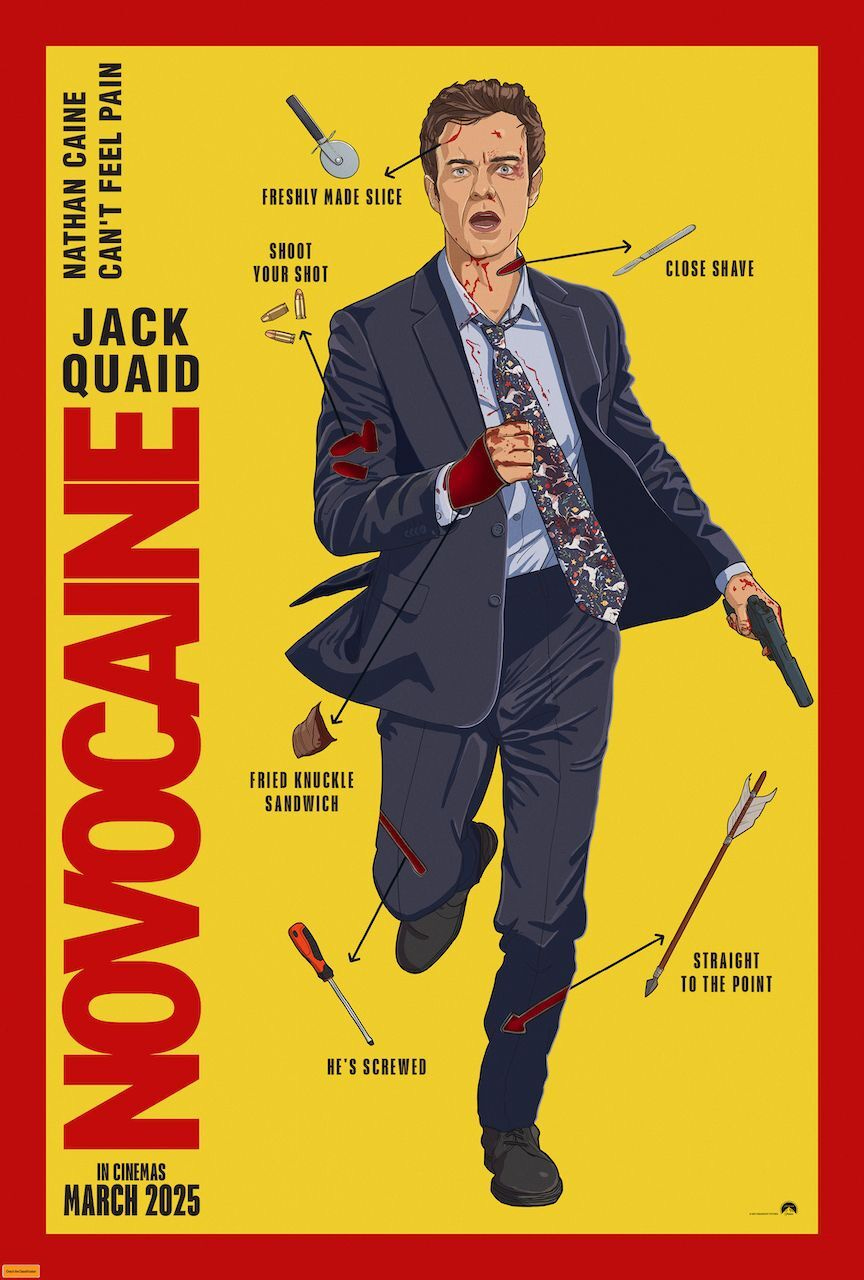

But why Novocaine? Why this tonally-compromised action comedy that can occasionally build a mechanically competent gag or set piece, but doesn’t seem to have the first clue on how to engage with its front-loaded theme of assumption versus reality?

Well, it’s because most of — if not all — the comedy wasn’t actually in the original script.

As mentioned earlier, I haven’t read the screenplay myself, but Novocaine’s directors — Dan Berk and Robert Olsen — did an interview with MovieWeb back in March, wherein they revealed that the original screenplay didn’t really have any comedy. This led to a comedic, “heavy-lift rewrite” of the script as part of the duo’s pitch to direct the film, but seemingly also because they just wanted to. The language here suggests both.

“It was definitely still an action movie, but it was a little bit more, I think, down the middle, tonally. There wasn't really any comedy, and that's something that we inject into all of our projects. We can't help but do that. And of course, the concept of a person who can't feel pain, who doesn't know how to fight, being thrown into an action movie is so audacious and, you know, such a sort of bombastic central kernel that we knew there had to be humor in it.”

"We knew there had to be a sequence in a booby-trapped house. We knew there had to be a torture scene where he had to pretend he could feel pain. So that was part of our pitch, to get the gig to direct. It was, 'We're gonna do sort of a heavy-lift rewrite and put all this humor into it.' We just needed that in order to get passionate about it. We had to make sure that we could kind of put our tonal print on it.”

Now, this wasn’t the worst instinct in the world. The concept of a regular guy who can’t feel pain whimming himself into an action hero situation does loan itself well to comedy, and the torture scene in particular is — individually — mechanically astute as a layered, irony-plus-subversion comedic beat.

But if you really pay attention to the energies of each scene in Novocaine, you can tell it wants to be a straighter action movie than a comedic one — just like the original script intended, per its alleged lack of comedy. Indeed, well over half film’s aggregated violence plays darkly and heavily, and the film’s villain Simon (Ray Nicholson) is presented as a cutthroat, unhinged, genuinely uncomfortable threat as opposed to an anthropomorphized obstacle for us to giddily root against.

An entire scene in Novocaine is dedicated to the bank robbers killing people, and the tone of it is venomous and mean-spirited — intent on making us feel the weight of the killing and the nastiness of the perps. This and plenty of other scenes are incongruent with the lightness of the action comedy that Berk and Olsen are trying to force Novocaine to be.

And this is even more clockable on account of the comedy in Novocaine being scattershot to the point where it’s clear that Berk and Olsen didn’t have a true comedic rewrite in mind so much as a few ideas to the tune of “Hey! This could be a funny thing that happens!”

Compare this to something like The Fall Guy, which was an action comedy right from the jump. Even its most violent encounters, murders and all, are played with full-body cartoonish cheese. The film knows we don’t need the straight, violent pathos to build tension, because the comedy already does that.

It also knows that that dark pathos would pointlessly conflict with the lightness of this particular breed of comedy, and so it instead pairs the comedy with similarly-light/endearing elements — like Colt’s wholesome love for Jody and her movie, or the cheeky thematic interrogations of the entertainment industry and how it treats people — to fill up The Fall Guy’s cinematic space.

If I were to venture a guess, it would be that Jacobsen’s original story was chiefly interested in being a sober rejection of fantasy. When you think of someone like Nathan Caine (Jack Quaid) — a guy who can’t feel pain — your mind probably jumps to a word like “superhero” or something similar to it, as Sherry’s (Amber Midthunder) did.

But, as it turns out, not feeling pain is actually incredibly destabilizing, because Nathan has to babyproof his house and not eat solid food so as to make sure he doesn’t impale himself on a table corner or bite his tongue off and bleed to death. This condition is not a superpower.

Nathan’s overly cautious lifestyle, however, means he doesn’t have much room to well and truly live. So, maybe he fantasizes. Maybe he plays a lot of video games. Maybe he’s hoping a woman will rescue him.

Then Sherry comes along, and all of a sudden he has something — a person and the emotions he has for them — real in his life; something that he can tangibly live for. Her “kidnapping,” then, forces Nathan to take risks (which we all need to do in order to live to the fullest) in order to save her. Subsequently, Simon — who has taken too much control of his life, so to speak — becomes a robust antagonistic foil.2

I’m nearly doubtless that the original story kept Sherry loyal to Simon, forcing Nathan to confront the fact that no one is going to save him from his life except himself, and perhaps also recognize that even if his relationship with Sherry wasn’t real, the emotions he felt were very much so. His emotions — the essence of who he is and his experiences — then become the proxy for himself, who he now realizes he has to live for. No more bubblewrapping, no more fantasizing.

The forced levity from Berk and Olsen kneecaps all of this. In Novocaine, Nathan’s condition is effectively channeled as a superpower up and down — he straight up punches broken glass so as to gerrymander Wolverine claws for himself, for crying out loud. Meanwhile, he and Sherry get a Hollywood happy ending, and he commemorates them “saving each other” with a tattoo of a knight and a princess rescuing one another.

All of this, on top of contriving a handful of premise-sensitive gags not because they serve the story, but because Berk and Olsen needed to do that to be passionate about the screenplay, regardless of how cumbersome they were.

And so here’s my question for the directors: if you need comedy in order to be passionate about whatever project you’re working on, why direct a screenplay that isn’t intended to be comedic? Why risk the essence of Jacobsen’s story to satisfy your own impulses (and they are impulses, make no mistake of that — momentary indulgences that don’t gel with the rest of the film)? Surely to God there was a pureblood action comedy script nearby that you could have directed instead.

I wouldn’t even say Berk and Olsen’s version of Novocaine is totally toothless, but the fact that I can so clearly see how much Jacobsen’s story would have thrived without Berk and Olsen’s insistence on comedy and levity, makes me quite sad. His screenplay has been bought, filmed, and dusted, and now Novocaine is forever confined to being realized as one of the more mediocre versions of itself on-screen.

If it were up to me, this fate would be far from final.

Now, I’m not one of those writers who believes that every script needs to stay as is out of some arbitrary respect to the writer. Cinema is a necessarily collaborative process wherein the goal is to create the best possible version of whatever story is being told, and the writer is simply the first step on that journey (albeit the most crucial one, since they supply the story in and of itself).

When I’m writing my screenplays, I find myself oscillating between writing a lot of direction and leaving it loose and open to interpretation, because making space for the visions of hypothetical collaborators excites me just as much as my own vision.

So, in order for the screenplay to thrive as a medium, the writer first needs to detach their ego from it, recognizing that the work stands not as a testament to the writer’s skill or mind, but to the potential of the idea that has just happened to find its way out of the ether via the writer.

On one of my current screenplays, I was prepared to leave off on an ending that worked well with respect to the ideas and emotions of the story, but then a better idea — the ending it currently has — came to me days later.

A director making a change to the screenplay is no different, so long as it serves the film and the story. As a writer, it would be irresponsible to handwring over weaker ideas just because they happen to be mine, just as it’s irresponsible of Berk and Olsen to weaken Jacobsen’s story just because they happen to like crowd-pleasing comedy.

And this — along with other reasons I’ll get to momentarily — is why I take issue with the “Written by” credit. Novocaine, for instance, credits Jacobsen as its lone writer, even though this is — in every way that matters — not the story he wrote. Audiences who know nothing about the industry will be none the wiser to what Novocaine was supposed to be, and all of a sudden, Jacobsen’s actual writing becomes lost to the noise, overshadowed by the commercial perversion with which it was cinematically realized.

That’s why, if it were up to me, I would have every film that makes significant deviations from the script credit their writers with “Based on a screenplay by so-and-so” instead of “Written by so-and-so.” Because that is, in essence, what’s happening — producers and filmmakers adapting a piece of writing for the screen, complete with deviations.

And it’s not like there’s not a precedent for it:

Psychologically, this would more firmly position/recognize the screenplay as an independent piece of work, rather than something that lives and dies by the non-guaranteed advent of production.

The next step would be to foster a cinematic culture around the screenplay’s recognized independence as a piece of art.

Because it’s no wonder writers can be so precious about their scripts; I consider myself pretty securely-attached to my writer identity, in that I’m always happy to prioritize the ethos of the story over what I personally want for it, but I’d still be scared shitless about selling it to the wrong people, like what happened with Novocaine. Not only did Berk and Olsen butcher the story, but now Jacobsen can’t even redeem the story with trustier hands down the line, because that screenplay is locked behind Paramount’s legal team now.

That’s why I believe in a world where writers are given more freedom and control over how they distribute and license and own their work. If we stopped treating the one production as the be-all end-all of the screenplay, and instead built a new status-quo that centers the value of the screenplay, writers might be less cagey about their scripts.

Let’s say, for example, that I license — rather than outrightly sell — one of my screenplays to Universal. The agreed-upon deal dictates that they have X amount of years to adapt the screenplay as a film, and I have X amount of years after the film releases before I’m allowed to license it out again.

Said film is their production, not mine, and so I have no involvement with it. As such, they’re free to do what they want with the screenplay for the sake of the production. Any changes they make are for the sake of the adaptation — the screenplay itself remains untouched.

If they so desired, perhaps I could get some extra work by coming on as the rewriter — if they want to make significant changes to the script, best to implement them using someone who knows the story being told, and can subsequently come up with the most harmonious ways to implement the changes while keeping the story intact.

Or, maybe the story of the screenplay needs to be broken to realize the vision of the film, and so the director just does the rewrites themselves — that’s okay too. Again, it’s their production, not mine, and maybe this will result in a strong story all its own (Challengers is a great example of this — Justin Kuritzkes’ original screenplay is much different than what plays out in the film).

But then maybe the film comes out, and the surrealist dark romance that is my screenplay has been adapted into a vibe-intensive, rollicking rom-com with a Sabrina Carpenter cameo and a protagonist that collects Minions merch. I’m irritated, because this is:

Not the story of the screenplay I wrote, nor…

…A surprise distant cousin of the story that’s equally thought-out and sincere.

But ultimately, it’s no big deal. The credits recognize that this film is based on a screenplay that I wrote, rather than actually being the story I wrote — blaming me for this creaky story would be like blaming Stephen King for bad Stephen King adaptations.

More importantly, my screenplay isn’t done and dusted once the credits of this movie roll. Maybe once my licensing agreement with Universal has been satisfied, I can license the screenplay to a smaller, more integrable studio that has a vested interest in serving the story, and then they come up with a film that more faithfully realizes my screenplay. Satisfied with their result, I tuck that screenplay away for good and keep shopping my other stories.

But it doesn’t stop there. Who says, after all, that film production needs to be the be-all-end-all of the screenplay? It’s ideal, yes, but can’t there be other avenues?

What about a culture where we can sell screenplays as cover-bound books? Perhaps in groups of three that have similarities in genre or theme?

Not only could this serve as a secondary financial avenue, but it could also offer a level of exposure and momentum that your screenplay might never find in the winds of Los Angeles. Maybe your book of screenplays blows up and finds a substantial audience, granting you a nice payout and maybe even being the catalyst for a production company to bite on it. Moreover, the name and content of your screenplay would be the market draw, so it becomes viable for them to make a deal with you directly instead of trying to rip off the story.

To that point, it might be true that we leave ourselves open to plagiarism if we choose to do this, but isn’t that what happens upon the very act of becoming a writer? Besides, having an officially-published screenplay/book of screenplays comes with its own copyright protections and publication date — if someone lifts the soul of your screenplay, you have a record that you were there first.

Remember when Simon Stephenson accused The Holdovers of plagiarizing his screenplay Frisco? Wouldn’t the truth of this case — whatever it is — be served better if it were published somewhere for all of us to read?

Even just as a reader, the idea of getting to read unproduced/not-yet-produced screenplays is just a fun one. You could find a whole sleeping-giant market of readers who are partial to screenplay-reading in a way that they maybe never were with prose, and ignite/reignite their cinematic passions with this sense of discovery — a screenplay not yet on the big screen. Theirs to imagine, theirs to be inspired by.

All of this, so long as we’re contextualizing it in a world where the screenplay is respected as an independent piece of writing — one that’s adapted for the screen as much as any novel, and one that its writer(s) are given proper control and ownership over.

Writers cannot thrive in a world where the screenplay’s obsolescence is a one-way inevitability. Let’s not live in that world.

This precedent, I think, would not only be a crucial component of NonDē, but an evolution of it. We go from filmmaking being grounded in non-dependence, to studios and bigger production companies becoming dependent on the blessings of the artists in a way that they aren’t right now.

And if you want to get extremely cheeky, we can hypothesize how this could all enable totally unique cinematic events. What if a writer licensed the same screenplay to two different studios for the purpose of putting two totally different realizations of it — different casts and crew all around — head-to-head at the box office? Moviegoers could follow the race of which production secures which actors and crew members, the trailers of each film would have a preview matchup of their own, and it would come to a front with a same-day release, Barbenheimer-style.

Luca Guadagnino’s Challengers versus Emerald Fennell’s Challengers

Scott Derrickson’s The Gorge versus Guillermo del Toro’s The Gorge

Jason Reitman’s Juno versus Nicole Holofcener’s Juno

Zack Snyder’s Dawn of the Dead versus Gareth Edwards’ Dawn of the Dead

Am I being totally naive, unrealistic, and chaotically quixotic here? Well, no, I don’t think so. If you’ll recall, all I want is for films to start saying “Based on an original screenplay by X” instead of “Written by X.” A fair and reasonable change to the status quo that’s actually much more consistent with the current realities of filmmaking than the current credit implies.

From there, the cards can fall where they may, and it just so happens that if we go the distance in realizing NonDē as the filmic infrastructure of tomorrow, we might find most of those cards falling right from the very intentional palm of our hand. Let’s go tell some fucking stories.

BY THE WAY: Any screenwriter reading this ought to check out the Inspired Screenwriting Competition, spearheaded by Filmstack’s very own

and ! The current (and final) submission deadline is July 15th, so if you have a feature script you’re confident about, prepare it for battle!I’ve got three originals and two adapted novels (the latter of which I approached with a tooth-cutting mindset more than anything), and I’ll be starting work on a new batch by the middle of the month.

This is present in the Novocaine we got, but is undercut by the rewrite’s decentralization of Nathan’s arc in favour of the spectacle of his condition.

This is largely a conversation for the Writer's Guild / union, who control crediting rules and rights - Studios and producers simply have to play along. Currently, a director has to re-write or write over 50% of a screenplay to recieve any writing credit alongside the original writer(s). This was put in place because in the past directors would almst by default knock off the original writer's credits and just claim it for their own...whether they had really changed all that much or not.

So for the example of Alien, Dan O'Bannon is the only credited writer in the actual movie credits. With a "Story by" Dan O'Bannon and Ronald Shusett. Walter Hill and David Giler are not officially credited in the movie AT ALL. And, unfortunately, how writers are credited determines how they're paid, so until/unless the Guild allows for a whole new style of crediting that isn't entirely tied to any given writer's livelihood, this is a question of more than just how crediting feels to us in terms of authenticity.

But I also, on a purely philosophical level, am not sure I agree that changes at any level of significance makes a screenplay "based on" a previous draft, rather than a tweaked version of that draft. Especially when it comes to tonal shifts - which can be executed predominantly in the direction of the movie and not at the script level - this becomes an iffy proposition. If I co-wrote a screenplay with three other people, there's still that element of 3/4ths of the screenplay not being my pure vision. That doesn't mean the others "based" their writing on my ideas or takes or vice versa. There's too much nuance being left on the table here, imo.

That all said, I wonder how much the 2018 movie THE MAN WHO FEELS NO PAIN, a Bollywood action comedy that hit it big at TIFF and did well in North America influenced how the directors (and likely the studio) thought Novocaine had to work.

Really I think the issue is in compartmentalizing genre elements, which is fine if you have a sharp vision of what you're making (which Berk and Olsen arguably did not).

I remember early on, I read an interview with the Duplass brothers, who I never really liked. They were talking about building a story by adding some drama and comedy and sprinkling them whenever they liked. I thought this was 100% false. EVERYTHING is drama. It's all drama, you never forsake drama. If you're making a full-on comedy, have confidence in it and move forward. But if you're making something like "Cyrus" don't shove some distracting "Step Brothers" business in there. Find where you can exaggerate the drama and let audiences find the joke.

Filmmakers used to respect audiences enough to find the joke. I'm hardly a fan of "John Wick", but those movies very delicately add humor -- mostly physical slapstick -- in a way that lets the audience laugh on their own, choose what is humorous. To go back further, the jokes in "The Graduate" are not universal laugh lines, everyone might laugh somewhere different.

I haven't seen "Novocaine", but what those guys are describing sounds a lot like losing confidence in the drama and finding ways to replace it with jokes, and then modulating the movie so they could toggle back and forth between drama (sadism, really) and gags, strictly a bid to keep the attention of restless audiences.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com