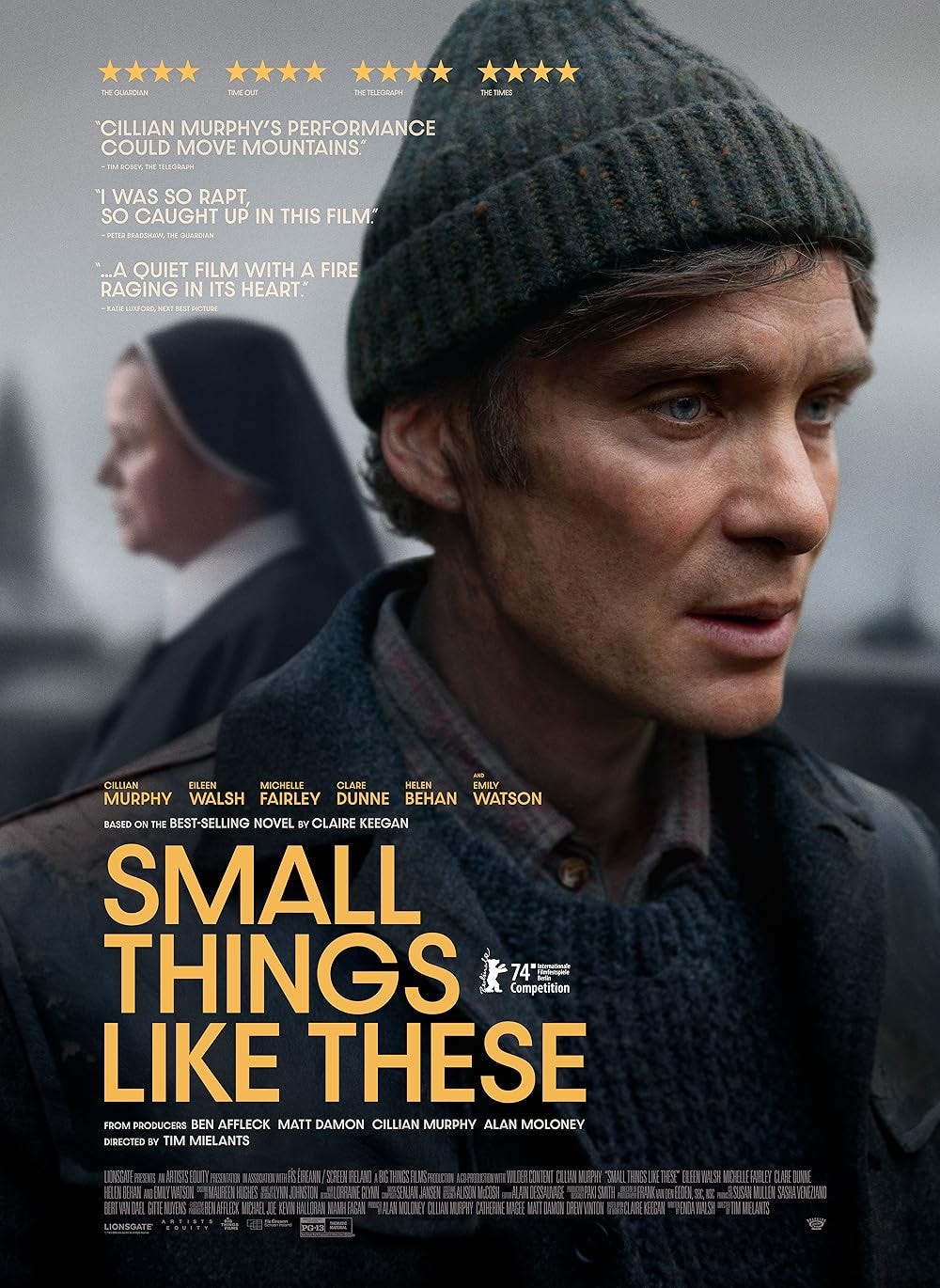

Like the unaffected-until-made-vulnerable bystanders living under any unjust rule, Small Things Like These — despite being marked as the main subject in the title there — will comprise just one of the pillars of this conversation. Just as well, because it’s going to be a heavy one.

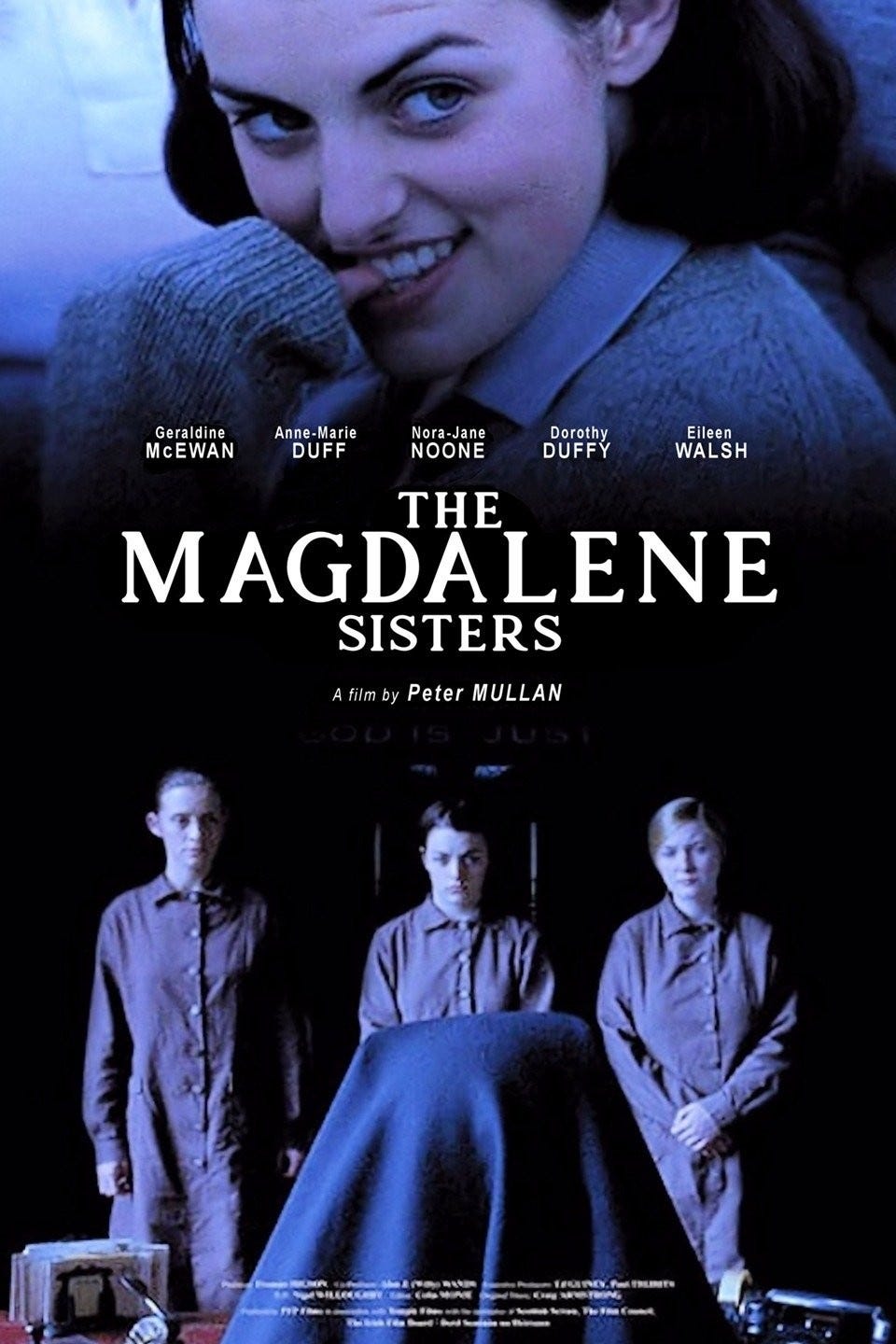

Today, we’ll be talking about Small Things Like These in relation to a film that it’s in tragically intimate conversation with — 2002’s The Magdalene Sisters. These two films, of course, in relation to the real-life subject matter that they deal with, which itself will be used to more widely contextualize the nature of oppression.

Set in 1985, Small Things Like These stars Cillian Murphy as Bill Furlong, a coal merchant and father of five daughters who begins to have misgivings about the laundromat that he regularly delivers product to, as well as the church that operates it — a church that also happens to have significant influence in just about every corner of the quiet Irish town of New Ross.1

In case you’re not aware, the subject matter in question here is the Magdalene asylums, a series of church-and-state-funded-and-operated laundromats that forcibly housed so-called “fallen women” in Ireland from 1765 until 1996, when the last laundry closed its doors.2

Now, you don’t exactly need the nose of a bloodhound to deduce that these institutions were abhorrent blights on humanity, but I’m going to save the specifics of the atrocities for a bit further down. This is because Small Things Like These takes an absolutely ingenious approach to the conversation of injustice, and it more-or-less relies on omitting the details of those injustices.

That is, we never actually see what happens inside the Magdalene asylums during Small Things Like These — the closest we come is when one of the inmates comes up to Bill and begs him for help before she’s aggressively sent back to her post by one of the nuns.

This may seem narratively counterproductive at first, but it must be understood that this forces Bill — and, more importantly, us audiences — to take these vulnerable women at their word about the horrors that are occurring in the backyard of this church state. To believe the accounts of people who are directly affected and targeted by said horrors.

Because here’s the thing, folks — if you wait around for hard, bubble-breaking evidence of injustice to thrust itself in your face before doing something about it, then chances are the proverbial3 cancer has spread a bit too far, so to speak. And when you consider that in tandem with the immense efforts of in-power institutions to suppress such evidence, it should be abundantly clear that injustice can only truly be fought from a place of active skepticism — with a steely instinct that something is wrong and a subsequent refusal to look the other way.

This is the thematic springboard for Bill’s arc, and the technical aspect of its presentation is no less astute.

After opening to a few shots of church towers standing oppressively over New Ross, we meet Bill going about his job, making his coal rounds in town. With every visit, the camera stays in his work truck even when Bill himself steps out to deliver. His bubble — his business — comprises only his most immediate interests of his work and his family, and he’s not poking his nose elsewhere.

Except, when he arrives at the local Magdalene laundromat to make his dropoff there, the camera instead opts to leave his truck with him, following him over to the shed where he delivers the coal.

By no coincidence, it’s here that Bill first begins to suspect4 that something is off about the laundry, as he covertly witnesses a young girl, Sarah Redmond, being forced into the laundromat by her mother despite Sarah’s desperate pleas and cries.

Here, the camera — and therefore Bill’s head — is no longer buried in the sand of his work, but is now questioning and challenging the reality that lies beyond his safe, familiar veil.

And what is that reality, exactly? Ladies and gentlemen, may I present The Magdalene Sisters:

Set in the mid-to-late 1960s and based on the accounts of real-life Magdalene inmates, The Magdalene Sisters follows four so-called “fallen women” — Margaret, Bernadette, Rose, and Harriet5 — as they try to outlast the hardship and abuse that took place at these laundries.

To be branded a “fallen woman” in the Magdalene days, one had to be witnessed or accused of doing one of the following (and, in all likelihood, this isn’t an exhaustive list):

Being a sex worker in then-poverty-stricken-with-no-social-welfare-program Ireland

Flirting with boys (which led to Bernadette’s imprisonment)

Having a child out of wedlock (which led to Rose’s imprisonment)

Getting sexually assaulted (which led to Margaret’s imprisonment, and is implied to have been a part of Harriet’s imprisonment).

Being an orphan

Getting disowned by your family

Not adhering to social norms

The majority of these “crimes,” by the way, came courtesy of the looser definition of “fallen woman” that was later adopted so as to more consistently staff the then-growing number of laundries, which profited off the free labour of these women (that is, the church profited off it).

Said profits would emerge as the focal point of these laundries, which, officially, were originally schemed up to lower prostitution rates and enforce social order.6 Go figure.

As for what exactly went on inside the asylums, accounts vary. The Magdalene Sisters depicts rampant physical and emotional abuse from the nuns, sexual abuse from the male priests, and an overarching culture of dehumanization wherein the women are hardly permitted to interact with each other. Real-life former inmates of the asylums claim that the conditions were far worse than depicted in the film, while others claim that the film over-exaggerates what went on, albeit without necessarily denying the inherent injustice of these institutions.

So, what really happened in the Magdalene asylums? Where’s the hard, bubble-breaking evidence that can guide us toward the objectively, morally correct emotional, actionable, and then legislative response? Where’s the green light for us to say “enough”?

Well, the year is 1985, so Bill and the rest of Ireland still have about eight years before the 155-strong unmarked grave is uncovered on the former land of the High Park Magdalene asylum, which had been sold by the owners, the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity, so as to cover financial losses from share dealings on the stock market. This discovery will cause a public scandal and lead to an unprecedented spike of first-hand accounts of physical, psychological, and sexual abuse within the Magdalene walls.

In other words, Bill has nothing to rely on but his instincts, which are currently and exclusively supplemented by the verbal and non-verbal desperation of these women. Even after the mass grave is discovered, it will only lead to more women saying the exact thing that so many other women have been saying for decades, if not centuries.

So either way, Bill’s lone weapon in this fight against the oppression of these women is his instincts. All he has to do is use them — really use them.

The midpoint of Small Things Like These is home to its most chilling sequence. During an off-schedule dropoff at the local laundry, Bill winds up inside the coal shed, where he finds a malnourished and sleep-deprived Sarah locked inside. She reveals that she’s pregnant, with her baby due in five-months’ time, and that the nuns promised her it would go to a good home.

This is a volatile moment. The camera is not steady in this scene — as it bounces between Bill and Sarah, the frame shifts around erratically to communicate not only the instability of this situation, but the possibility of freedom it represents as well.

Indeed, just as Bill is in danger of being caught snooping where the church doesn’t want him to, so too is there a precious, dwindling window of opportunity to rescue Sarah from this institution while no one’s looking.

Dynamism of the camera = dynamism of the circumstances

Freely-moving frame = potential for a freely moving Bill and Sarah

But something — be it his shock, his fear, or his desire to witness the inside of the Magdalene asylum with his own eyes, perhaps in hopes of confirming what he knows to be true so as to gain a sort of pseudo-permission to act — gets the better of Bill, and he leads Sarah out of the shed and back to the laundromat, where the nuns feign ignorance to her prior whereabouts and pretend to take care of her.

Bill, however, is not let off the hook so easily. He and Sarah are brought into the office of Sister Mary (Emily Watson), the head nun of this laundry, where Sarah is none-too-subtly pressured to blame her coal shed imprisonment on a hide-and-seek game gone awry. We, of course, are expected to realize that the nuns locked her in there.

And where the camera during the coal shed scene was buzzing with a sense of danger inherent to the possibility of freedom, the camera in Sister Mary’s office is stiff and steady, moving only with a controlled drift while mostly keeping the frame completely still and rigid. Within the walls of the laundry, the possibility of escape has been smothered and locked down, replaced with the oppressive order of this taut frame. Bill has dropped the ball on his first real chance to act.

To make matters worse, Sister Mary also ominously suggests to Bill that his family — specifically his five daughters — could have a rough time of things at their nun-run school if he makes public the truth of the laundries. She bookends this with hush money masquerading as a Christmas gift for Bill and his wife Eileen.7

As his conscience deteriorates throughout the film, Bill finds himself in a handful of conversations about the injustices of the church — with Eileen, with his friends, with whoever will spare him a moment — but he’s faced with the same demoralizing sentiment every time; the church controls nearly every aspect of New Ross, and if Bill speaks up, he’ll only succeed in putting a target on the backs of his daughters, and the Magdalene inmates of present and future will continue to suffer. Bill, so says his confidants, should just focus on his responsibilities and be grateful it’s not his family being brought to harm.

The question, then: what can Bill do? What power does Bill have to meaningfully counteract the oppression of the Magdalene regime without having it be overshadowed by the targeted retaliation of the church on his uninvolved daughters?

Well, near the end of the film, Bill finds himself trudging on a whim to the laundromat, where he instinctively checks the coal shed. Sure enough, he finds Sarah there, but this time, he simply assures her that she no longer needs to be afraid.

He then helps her up, guides her back into town — in full view of those who urged him to look the other way — and brings her into his home, safe from the asylum.

Something similar happens in The Magdalene Sisters, when Margaret gets out by way of her brother Eamonn, who was just a small boy when she was taken away to the asylum, and who signs a release for her so that she can leave freely.

In other words, all it takes to save a life from the Magdalene institutions is a very, very simple act of compassion. Bill and Eamonn exemplify this.

It’s no substitute for the mass indictment and dismantling of the system that empowers the church and the Magdalene laundries, but Bill’s action — the titular small thing — makes a difference here. Indeed, while realism and personal vulnerability must always be accounted for in any fight like this, it remains that there is always some degree of individual power that can be maximized in the face of any oppressive regime.

One day, that power will take the very potent shape of the journalist who will break the mass grave story. Today, it’s taking the shape Bill, whose power likely caps off at saving Sarah. Tomorrow, it might take the shape of an Eamonn. The next day, it might take the shape of a Bill and an Eamonn.

All of these things matter. Protecting a human being matters. Denying any and all space and opportunity for these autocratic mandates of exploitation, dehumanization, crippling social order and erasure, and manipulation via fear matters. Breaking free matters. Waking people up matters.

And make no mistake; what happened at the Magdalene laundries is cut from the exact same cloth as the systemic injustices and authoritarian campaigns all over the world, very much including the ones we’re staring in the face at the moment.

One of the most illuminating moments in The Magdalene Sisters is a very quick scene wherein the whole convent — nuns and inmates alike — gather for a religious ceremony of sorts, where the priest bestows his blessings upon someone or something.

We don’t actually see who or what he’s blessing until he finishes up and the convent begins clapping, at which point we’re greeted by a shot of brand new washing machines.

“Machines” is the operative word there — of course the priest would bless the machines that comprise the new infrastructure of the laundries, because these laundries only ever existed for the sake of the institution and the heinous control that they perpetuated.8

The most extreme antithesis of these oppressive institutions are women like Bernadette, the greatest narrative weapon in The Magdalene Sisters’ arsenal.

Bernadette’s storyline in The Magdalene Sisters almost reads like that of an antihero. She’s the one who’s always plotting to escape, and attempts to do so many times, convincing a reluctant Rose to come with her during her final (that is, successful) attempt, and physically fighting back against the nuns when they try to drag Rose back into the asylum. She later helps to arrange Rose’s escape to England while Bernadette remains in Ireland, now protected from the nuns thanks to her hairdressing apprenticeship given to her by her cousin.

It’s clear that Bernadette’s disillusionment is as potent as her compassion, right? Well, not everyone would agree. When Katy — an elderly inmate who believes that these laundries are doing right by society and by God, that the nuns care about the inmates, etc. — falls ill, Bernadette is charged with taking care of her, and she has very little patience for this woman who thinks any of this is okay, going as far as telling Katy:

BERNADETTE: The Sisters just want the work done, or have you not figured that one out yet? Your father was right. You must be thick in the head if you've not got that one. The Sisters don't give a toss abut you and neither do I. So just do them and me and the whole world a favour and shut up and die.

Later, after Katy has died in the infirmary, Bernadette discovers her corpse — still fresh with tears — and kisses her forehead, whispering “it’s what you deserved” so as to guard her own emotions.

Bernadette’s is a radical sort of love that some might not understand. Maybe she doesn’t understand it herself. Her anger is with those who smother humanity and freedom in favour of submission and order, including those who are psychologically complicit in smothering their own humanity, such as Katy.

Pay attention to:

How Harriet changes when she misplaces her St. Christopher locket.

The timeline of Bernadette hiding said locket from Harriet.

Margaret’s reaction to finding out that Bernadette had been hiding it from Harriet.

The reason Bernadette names for hiding the locket from Harriet.

How Harriet changes after having her locket returned to her, both in relation to how she was before and during the loss of the locket.

The other question, then: how do we help those who don’t realize that their humanity is being exploited? Can we save those — and, indeed, humans as a whole — who do not understand that these limitations are contrived façades, or who do not believe that there can be more to life?

What does it take for an individul to not only recognize the needless tragedy inherent to these systems of fear and injustice, but to stop submitting to them?

It’s officially estimated that 30,0009 women were subjected to the horrors of the Magdalene laundries, but those are just comprising the known records of the 19th and 20th centuries — between missing information and the church’s continued insistence on secrecy, nearly a century’s-worth of Magdalene inmates have been lost to time, forever silenced by a reactionary, institutional social order defined by fear and a perverted sense of purity.

Uniting both of these films — and, indeed, most every story that resonates across time — is the fact that human beings deserve to be free, and that humanity’s lone enemy is the forces that seek to victimize and stratify us against each other, as though any life lived with fear and cynicism towards our fellow humans is worth living.

SISTER MARY: For as the heavens are high above the earth, so strong is His love for those who fear Him. As far as the east is from the west, so far does He remove our sins… As the Father has compassion on His children, the Lord has pity on those who fear Him; for He knows of what we are made, He remembers that we are dust… The love of the Lord is everlasting, upon those who fear Him; His justice reaches out to children’s children, when they keep His covenant in truth…

Because, folks, the moment we begin to operate from a place of fear and caste — in service to a monolithic, unfeeling, self-serving entity rather than each other — is the moment that we begin to lose our way. That’s what caused these women to be sent to these mass-grave-inducing labour camps on the charge of getting raped. That’s what enabled the systemic extermination of Jewish people. It’s the seed of the mass slaughter of Palestinians and Persians. It drove the slave trade and the ethnic cleansing of Native Americans. It enforces the oppression of Dalit Indians, the erasure/demonization of trans people, and the culture of fabricated scarcity and artificial competition inherent to this capitalist economic system.

Every war, every genocide, every prejudice, every insistence upon poverty; it all links back to fear. Fear that we can only be more if someone else is less. Fear that our way of being might not be correct, and so we purge all other ways of being to make our own way correct by default. Fear that we will become lost in our individual freedom, so we seek to submit to something else. Fear that human beings are so fundamentally bad and selfish and evil and depraved, that we can’t be trusted to be free, and so must be controlled by a machine-like system, because a machine can’t be wrong, right?

This is no way to live, and sure enough, if we keep centering fear like this, we will die, at which point Bernadette will kiss our collective forehead and whisper “it’s what you deserved.”

And, despite absolutely everything, she will be wrong.

It goes without saying that I won’t be speaking too kindly about the church here. Out of respect for any of my practicing Catholic readers, I want to clarify that I don’t believe the church as a concept is inherently evil, but as an institution, it’s categorically amoral, and so its doctrine can be (and has been, many times) weaponized to a disastrous degree. When I refer to the church, I refer to the church purely as an institution.

Curiously, Small Things Like These names 1998 as the year that the final asylum closed its doors. Whether this is an error on their part, or the producers have information that all my other sources do not, I do not know.

(but also not so proverbial)

This is just insofar as the runtime of this film is concerned. In all likelihood, he’s had these misgivings for a long time, and is simply approaching his breaking point.

For most of the film, Rose and Harriet go by the names given to them by the nuns — Patricia and Crispina, respectively. I’ll be referring to them as Rose and Harriet for obvious reasons.

Surprise, surprise; prostitution rates did not lower.

Played by Eileen Walsh, who also portrayed Harriet in The Magdalene Sisters. I’m choosing to believe this is no coincidence.

Ironically, there’s a good to fair chance that washing machines — nullifying the need for most of the physical labour along with being available for home purchase — played a role in rendering these laundries financially obsolete.

Similarly to footnote #1, Small Things Like These puts the number at 56,000 women. This, again, contrasts with most all the sources I’ve perused on the topic, but — for reasons that I’ve included in this very paragraph — I have little trouble believing that 56,000 is the more accurate number.