The Intricate Comedic Identity of 'American Fiction'

Plus, a how-to on approaching comedy films with the new film criticism

Here’s a pair of Polar Pop-cold takes to kick us off: American Fiction is superb, and comedy is one of, if not the single most difficult artistic nut to crack, especially if you’re delivering it by way of cinema.

This is true of the craft, and this is true of critiquing it. Comedy is beholden to subjectivity to a degree that most other components of film are not — you can laugh at a joke in the same way you can be dazzled by a camera angle, but you can posit a purpose for a camera angle so as to appreciate it or discuss it more objectively. You can’t do that with a joke, because the purpose of a joke is to spark joy or otherwise tickle your sense of humour — to elicit an emotional response that’s exclusively relevant to you, and is therefore moot as a point of discussion.

To that point, should comedy films even be subject to critique? Comedy films primarily traffic in joy, whereas most every other genre primarily traffics in ideas and perspectives. These things can be examined and interpreted with objectivity in a way that joy can’t, so is it even possible to objectively examine the very cinematic organisms that create such joy, if not in one viewer, then in another?

Well, yes, actually. We may not be able to objectively wax on an individual gag’s funny-factor, but we can objectively examine the frameworks that enable the gags. By doing that, the analytical goalposts change — not by how funny a film is (which is inescapably subjective and therefore impossible to analyze), but how cohesively it inhabits a comedic identity.

We can examine the function of a comedic framework and appreciate that, even if we don’t laugh at the joke.

Similarly, we can — and do — examine the function of a camera angle and appreciate what it does/conveys, even if we don’t like the technique, or even the intent.

But again, to what end? Haven’t we immediately lost the plot if we’re not talking about how funny something is? No, because we can’t actually talk about how funny something is, because that’s unassailably subjective.

If we’re trying to critique film — with the end goal of helping future filmmakers approach their craft more thoughtfully and intentionally — we need something we can actually talk about, and what we can talk about in comedy films is the frameworks that create a film’s comedic identity.

Consider, for the sake of example, any given streaming-original film that employs comedy in its genre cocktail. Most all of the gags aren’t any more involved than the characters saying or doing what’s obviously intended to be a funny thing, amounting to a film that just fires off random gags and one-liners in hopes that the majority of them stick the landing. These films have no ownership over their comedic identities — they’re simply trying to make people laugh without really considering what they believe is funny.

And it should go without saying that films need their own identities; something that the audience can bring themselves to and interact with. Without an identity, the film is nothing more than a product. This applies to every film ever, not just comedies.

Now consider something like Superbad, which does have a cohesive comedic identity rooted in an observable mechanism (in this case, tension and release), often with Seth (Jonah Hill) as the main cog. Fogell does or says something stupid? There’s the tension; now we’re waiting on Seth to lose his shit so as to give that release. Evan and Seth get to talking about sex? We tense up knowing that Seth is going to say something outrageous, and we get that release when he finally does.

Sure, maybe you think the stuff that Seth says is funny. but maybe someone else doesn’t. Both of you would be correct. How, then, can Superbad be useful material for a wannabe comedy filmmaker?

Because it has a framework — an observable operation in the film’s comedy — that can be studied, learned from, and iterated upon.

And tension-release is just one framework.

There’s subversion, wherein we expect something, and then are caught off-guard when those expectations are shattered, resulting in laughter (Feathers McGraw’s jailbreak scene in Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl is a fantastic example).

There’s irony, where exchanges are humorously punctuated by one or more characters not being in the know of certain situations or elements, thereby adding an unintended double meaning to their dialogue that we audiences then laugh at (pretty much all of Back to the Future).

There’s transmuted levity — an iteration of tension-release wherein a scene’s somber, sentimental tone provides a powerful, fertile emotional base that a sudden comedic beat can then play upon to elicit laughter as a release (A Real Pain, when Benji and David are making their final rooftop visit before they fly back to America, and David says to Benji: “…you light up a room and then you shit on everything inside of it”).

If a comedy film consistently functions within one of these frameworks,1 then it’s consistently appealing to senses of humour beyond the writing of the gags, and has a comedic identity to call its own.

When a film has a comedic identity, it seeks laughter with a magnet rather than a sledgehammer. It knowingly attracts laughter with the science of its framework, rather than grasping at laughter with hopeful but unfocused one-liners.

If it’s a particularly impressive comedy film, its beats can function in two or more frameworks at once so as to tickle even more subconscious funnybones.

And if it’s as ingeniously crafted as American Fiction? Well, it can coalesce these frameworks in a way that I’ve never seen another comedy film do before.

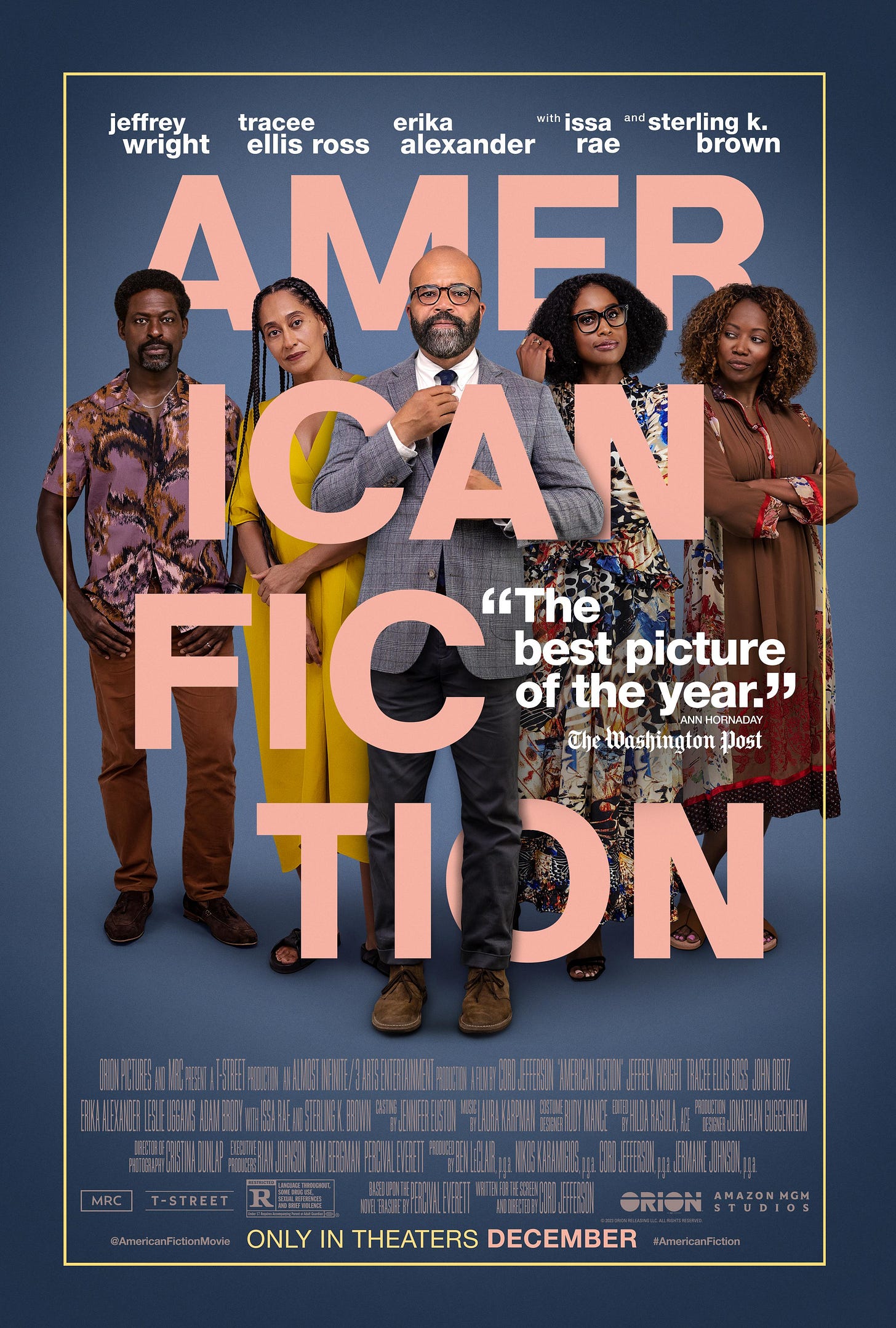

Yes, after that obnoxiously long intro, I’m finally talking about the actual subject of today’s piece of criticism. The first scene of American Fiction involves our protagonist, Monk (Jeffrey Wright), teaching a course on the literature of the American South. During the class, a white student voices how offended she is about seeing the n-word written on the board.

This white woman, of course, does not realize how big of a fool she’s being by pearl-clutching over something that is not significant to her experience as a white person, all while the Black students and the Black professor are taking absolutely no issue with having the word on the board in the context of this particular college course.

MONK: Listen. This is a class on the literature of the American South. You’re going to encounter some archaic thoughts, coarse language, but we're all adults here, and I think we can understand it in the context in which it's used.

BRITTANY: Well, I just find that word really offensive.

MONK: With all due respect, Brittany, I got over it. I’m pretty sure you can, too.

BRITTANY: Well, I don't see why.

Right away, we have our main comedic framework (or comedic identity) — irony, where we’re responding to certain characters speaking with utter obliviousness to what we know to be true. As you’ve seen here — and will continue to see momentarily — that “thing we know to be true” is almost always their own ignorance.

This irony-centric comedic identity continues to establish itself with the primary hook of American Fiction: Monk — perpetually disdainful over a literary market that won’t accept Black stories beyond gross stereotypes — writes a “joke novel” that’s plastered up and down with said stereotypes, only for the market to gobble it up and hail it as a straight masterpiece.

He’s dumbfounded, but still takes the resulting $750,000 payday (plus an eventual $4 million movie deal) to help care for his ailing mother. He writes this novel under the also-satirical pseudonym of Stagg R. Leigh, who he’s then tasked with impersonating when the book blows up. This persona — an on-the-run convict who “dresses street” — is, of course, nothing like Monk.

Here, we have two irony frameworks — not only do we laugh at how oblivious these white publishers and authors and producers are to the fact that the book (titled My Pafology, later Fuck) is meant to be intentionally-offensive satire rather than a “brave, raw, real” account of Blackness, but we also laugh at these same people responding to Monk’s Stagg persona, which we audiences know isn’t the real Monk.

Both of these frameworks flow from that aforementioned, ironic comedic identity, which we know is the identity because of the irony that’s baked into the film’s hook — that self-serving everpresence is what we’re looking for.

But rather than each beat — each comedic line — working in both of these ironic frameworks at once, the beats instead work in just one framework while being secondarily informed by the other.

When Monk, as Stagg, goes to meet film producer Wiley Valdespino (Adam Brody), Wiley — while briefly discussing “Stagg”’s “prison sentence” — remarks on how he himself spent a month in prison for interstate commerce charges, which apparently opened him up to diverse experiences (by which he means people of colour, not realizing that such experiences are obviously much more diverse than being in prison).

WILEY: Just don’t see too many convicts drinking white wine.

MONK: You know many convicts?

WILEY: You’d be surprised. I spent a month in the joint myself. It was some interstate commerce shit. It was a short stay, but I’ll tell you what: That experience grounded me. The people I met in there allowed me to see a whole new world of underrepresented stories from underrepresented storytellers.

We laugh because Wiley has no idea how utterly foolish he’s being when he says that. That’s irony — the framework that this beat operates in.

But that same beat is also informed by the other irony framework — Wiley not being aware that Monk’s Stagg persona is an act — even though the beat isn’t actively utilizing that framework.

When Wiley talks about his own prison sentence, he isn’t directly responding to Monk’s Stagg persona, and so the irony of Monk actually being nothing like Stagg isn’t directly leveraged by this beat.

Instead, the precedence of Monk’s Stagg persona is supplementing the other irony framework of white people not knowing how ignorant they’re being.

To put it plainly, American Fiction believes irony is funny, and irony is therefore baked into every gag it makes, even if the gag itself isn’t primarily ironic. In this way, the gags flow out and dance between different frameworks without ever fully detaching themselves from that ironic core. This diversifies the comedy without jeopardizing the comedic identity.

Meanwhile, if you had a separate framework that had nothing to do with that ironic core, you risk a clash that could muddle the comedic identity. American Fiction is careful not to do that.2

But the above example is limited, since the two frameworks in play — despite being separate — are both irony frameworks, and therefore aren’t terribly distinct from each other or the ironic comedic identity. Luckily, a better example just happens to be…

…one of the best beats in the entire film.

Around the middle of American Fiction, we’re dropped into a phone meeting between Monk (again as Stagg), his agent Arthur (John Ortiz), and a pair of white publishing agents who love Fuck and have no idea that it’s meant to be a joke. While listening to the white agents talk nonsense, Arthur makes a gesture at Monk wherein he pretends to blow his brains out because of the stupidity of this conversation, but then immediately, sheepishly apologizes when he remembers that Monk’s dad committed suicide in that exact manner.

By making that gesture, Arthur destroys the framework of the beat by actively pointing out to us, in the middle of the beat, how ignorant these people are. In doing so, he kneecaps the role that the audience plays in bringing comedic irony to life, which is normally a big comedy no-no.

That’s like if Marty McFly said something like “It sure is awkward to hear my future grandparents tell my future mom that my parents are probably idiots, since they don’t know I’m actually her son.”

So there we momentarily sit, disappointed that Arthur ruined the joke with what, at first, seems to be a loud, lazy bit of audience-winking comedy. But then, it turns out to be a setup for a whole other beat (the awkward apology for fake-shooting himself when Monk’s dad real-shot himself).

In other words, the film catches us off guard by taking what we subconsciously understood to be a line that tries to be funny but just ruins the joke, and revealing it to actually be a setup for a completely different joke. That’s subversion — another type of framework.

But it doesn’t end there — the gag that this subversion gives way to utilizes dark comedy, which itself has roots in the framework of subversion. This, while still maintaining a connection to the film’s core comedic framework of irony (by way of the conversation with these white people). This is objectively intelligent comedy writing.

You see? It’s not possible to critique the dialogue of the jokes so as to analyze their funny-factor — some will laugh at Arthur’s apology, others won’t, and that’s all there is to it.

But by examining the science of comedy as a craft, we can talk objectively about comedy films and the very real, if still limited, control that they can have over their own mileage. American Fiction’s science just so happens to have a remarkable plethora of bells and whistles.

Even more impressively, this transient, baton-like flow between comedic frameworks shares a direct relationship to American Fiction’s dramatic and technical aspects. Laura Karpman’s jazz score goes beyond the obvious allusive component (the film’s protagonist is named Thelonious “Monk” Ellison) — by trafficking in a genre as definitively spontaneous as jazz, the score mirrors the lively, diverse, and dynamic organism of American Fiction’s comedic thrust.

Meanwhile, the requisite for American Fiction’s foundational irony framework — i.e. something not being known — is not only the exact frustration that Monk harbours, but also his own greatest vice. Indeed, just as he rages against a machine that refuses to see/know diverse Black stories, he’s also too prideful to meet other people where they’re at and, by extension, allow those people to really know him.3 Being known, of course, is how love happens.

Monk demands the publication of richer Black stories, and yet cuts himself off from the source of his own emotional richness — his family.

And that’s the thing about love, isn’t it? That we choose to love people even when we can’t stand them sometimes? Even when their spikiness or mere benign contrasts disrupt us to the nth degree? Indeed, how much pride and authenticity must we give up for love and connection?

Similarly, how many independent comedic frameworks can you accept without popping the bubble of your comedic identity?

Ladies and gentlemen, may I present to you Sterling K. Brown, who plays Monk’s brother Clifford “Cliff” Ellison.

Monk and Cliff share a lot of funny exchanges that are intended to be funny, but are not primarily intended as full comedic beats. The first conversation they have after Lisa’s death is the perfect example — it contains plenty of humour, but it’s tense and loaded. This conversation is not a comedic beat for us, but a moment of intimacy for them as brothers that just happens to have some funny dialogue.

Here, we have an example of a new comedic framework that also has nothing to do with the ironic core — humour as characterization and helping us understand relationship dynamics. The laughter we get out of the dialogue is a side effect of us becoming more intimate with these characters and honestly investing ourselves in them. It’s a sweeter, more emotional laughter than the straighter side-splitting of more traditional comedic frameworks — the way you’d laugh at a puppy discovering a bad smell for the first time, as opposed to the way you’d laugh at a comedian.

But, again, this framework has nothing to do with American Fiction’s established ironic core — none of this humour originates from white ignorance. By having nothing to do with that ironic comedic identity, this framework threatens to clash with it, just as Cliff clashes with Monk.

And indeed, during a trip to see their recently-homed mother, Cliff probes Monk on where the hell he’s getting all this money to pay for their mother’s care expenses. Monk, taking caution to guard his secret identity of Stagg R. Leigh (standing in here for the film’s overarching, ironic comedic identity), pushes back and doesn’t disclose anything, which is also just typical, close-yourself-off, drift-away Monk behaviour.

Cliff isn’t done probing, though. At Lorraine’s wedding, he says to Monk:

People want to love you, Monk. I personally don’t know what they see in you, but they want to love you. You should let them love all of you.

And then he sweetly kisses Monk on the forehead. Monk’s prideful bubble has been popped, and he’s better for it.

Similarly, the unattached comedic framework that exists in Monk’s and Cliff’s siblingship threatens to pop the bubble of American Fiction’s irony-centric identity, but the film is ultimately better for that other presence because of how deeply it informs the dramatic, emotional core of the story. That irony-centric comedic identity, after all, is just one part of American Fiction’s diverse cinematic nutrition profile.

Another way to think about this is that Monk and American Fiction both define themselves in relation to white ignorance, even though they can and do define themselves with so much more (i.e. the familial aspects) than just that. This is the arc.

And there’s so much more I could talk about and touch on and point out, but I can’t call myself a disciple of the new film criticism if I don’t allow room for audience discovery. I never mentioned Monk’s mother Agnes (Leslie Uggams), Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), or the film’s Shakespearean sheen, and how they all tie into American Fiction’s delicious comedic equation as well.

This, partly because I don’t want to overstuff this piece, but mostly because I’d rather you make those observations on your own. I try and leave my critiques non-exhaustive precisely so that we can exhaust a film’s critical potential together, insofar as a film is capable of being critically exhausted.

The new film criticism, you see, is determined to have us supplement, contradict, challenge, and coexist with each other, and we accomplish that not just by talking — but by actually wanting to talk. To understand in hopes of expanding, rather than respond in hopes of stagnating. Humans informing the essence of humans, films informing the essence of films, humans and films informing the essence of each other.

Indeed, if we can relearn how to include the film itself in conversations about film criticism, maybe we can relearn a few other things, too.

Or other frameworks that I’ve neglected to mention here.

Except when it has a good reason to do so, which I’ll touch on in a minute.

This, also none too subtly symbolized in his pretending to be Stagg R. Leigh.

I think this is a great analysis of the jokes in this movie, but I do wish the entire movie followed these prompts, for lack of a better word -- the sentimentality feels like a gutless backtrack compared to the book. I'm a big fan of Percival Everett, and this adaptation is considerably less manic than the book.

I will add that I don't think I've read anyone say anything about the commentary of casting Adam Brody in this particular role, since for years he was an actor stuck playing The (Really) White Guy in a series of movies with predominantly Black casts. Like he wasn't just playing a white guy in those movies (which were frequently a dime a dozen), he was playing THE white guy. For me, it added another layer to every gag in which he was involved. But again, perhaps I'm adding a layer of cinema literacy that just isn't there.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com

Great insights on the workings of comedy, and I especially love the phrase "intelligent comedy" (aka recognizably functional comedy vs. just what any rando personally finds funny.)

I've long argued to writers that comedy is a specific skillset, that most people really can't just "write a rom com" or a satire when they've never focused on the genre before. This rarely seems to stop them from churning out stories stuffed with obvious situational and potty humor and little else, sigh...

It also explains why extremely "conservative" or "right wing" comedy for the most part doesn't exist to larger audiences - they say reality has a liberal bias, and so this POV of what's funny is often anti-irony, or inverse irony, the context that would make it intelligent comedy flipped on its head to where it's just mean-ass taking points that some people will laugh along with but there is no structural humor to be had there, and in fact a funhouse mirror distortion of it.