2025 Oscars Round Table: The Charlotte Cut

Electric Boogaloo: Tokyo Drift (Taylor's Version) & Knuckles

In case the carrier pigeons went on strike in your area, I had the pleasure of taking part in a 2025 Oscars Round Table spearheaded by the decidedly lovely

, where I joined a ragtag pack of FilmStackers1 in dissecting the “will,” “should,” and “would” of all the categories from A to W (Writing).Highly recommend you check it out here sooner rather than later!

Apart from myself and Maria, the Round Table also consisted of

, , , , , , , , , , and .I was recruited to talk about the nominees for Best Original Screenplay and Best Adapted Screenplay, one breakdown per category at 150 words apiece. I do not exaggerate when I say that working within that word limit was the most harrowing challenge of my entire life, surpassing the oppressive gauntlet of virulent-to-legislative transphobia and steering this body with what I now understand to be a bipolar brain.

Okay, I’m exaggerating a little — it was only the second most harrowing.

Anyhow, what follows is a version of my Round Table takes that aren’t beholden to that collaboratively necessary word limit. Plus, a few other Oscar and Oscar-adjacent thoughts to round out my awards season sentiment ahead of the big night.

A Quick Word on the Oscars as a Whole

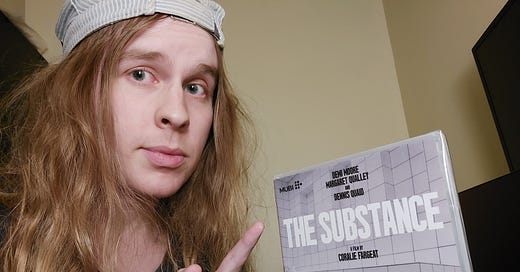

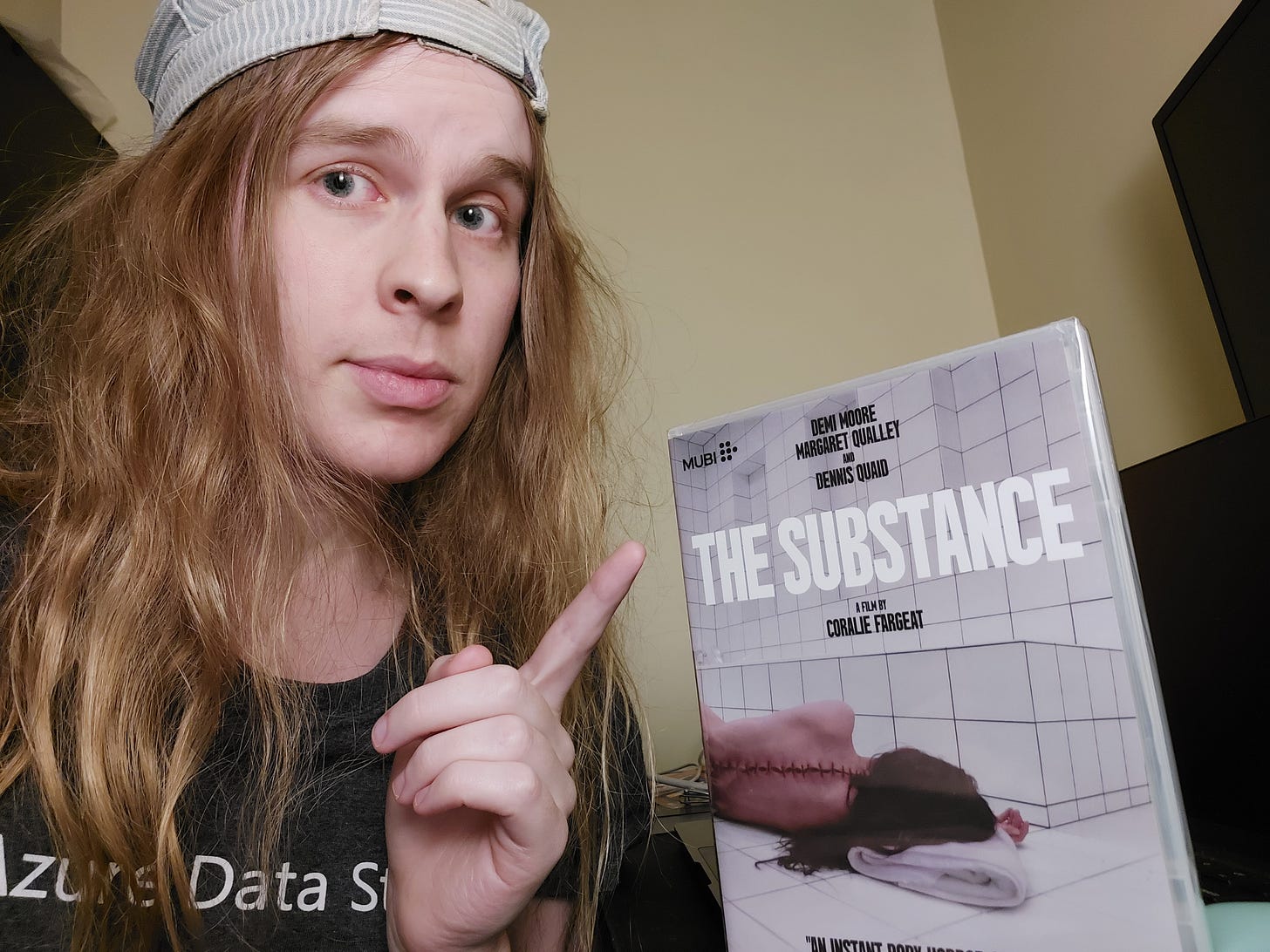

Here’s the truth: I think it’s an absolute blast to get behind a film in each of these categories and watch the ceremony play out like a football game, where your passion for the victory or loss is driven by a blind and nebulous but nevertheless potent attachment to the film that you’ve adopted as your own. In my case, this would be The Substance or Sing Sing.

Here is another truth: I genuinely do not give a single solitary hoot if The Substance walks away with nothing. I love the sugar rush of the Oscars and will cheer and mope accordingly with Sing Sing’s fortunes, but what I believe in is a world where we don’t allow filmic recognition to be defined by competition. The Oscars, as they are now, allow that, which is how we devolve into cynical infighting over snubs and “unworthy” nominees, thereby distracting from the meaningful connections we could instead be making through all of these films.

I would gladly see the Oscars dissolved if all of that money went into promoting and otherwise funding/expanding the THR Round Tables, Actors on Actors, and other such initiatives that focus on the aforementioned recognition of the art without the hierarchical element of the Oscars.

That said, you’re going to see me use language like “what/who is the best” and “so-and-so deserves this over that” in this piece. I’m using that language for the sake of not getting too pedantic, but know that my true thoughts/feelings on the hierarchization of art are as outlined above.

I won’t stay on this too much longer. All I’m saying is, everyone complained about Margot Robbie’s Barbie snub, but very few attempted to ask what Robbie’s character — and Barbie more broadly — might think of how heavily our culture values non-falsifiable competition.2

Now, let’s hop into the Charlotte Cuts!

Best Original Screenplay

Contenders: Anora, The Brutalist, A Real Pain, September 5, The Substance

Who Will Win: The Brutalist

Who Should Win: The Substance

Dark Horse: A Real Pain

Snubbed But Not Forgotten: Babygirl

Coralie Fargeat already has the Cannes Best Screenplay award under her belt, and there’s frankly no reason that The Substance’s pages shouldn’t also translate into a Best Original Screenplay win at the Oscars. Reading the script is almost as engrossing as watching Fargeat bring it to life on screen, and also offers new ways into the myriad of themes that she plays upon in the story. This, all while reminding us that the indigestibility of the film is a key part of its genius. To speak candidly, the depth of thought within and robust presentation of The Substance’s script puts it head and shoulders above its competitors, all of whom house elite storytelling chops in their own right. Still, The Brutalist — the clear juggernaut of this season — will probably steal it away, even though the screenplay likely illuminates the argument that Brady Corbet’s talent as a filmmaker is, paradoxically, The Brutalist’s biggest weakness.

I’ve said mostly all I was interested in saying about The Substance sans a layout of its themes (which, as I touched on several pieces ago3, primarily traffic in the dichotomy of comfort and love, how the former ruptures our capacity to embrace and create the latter, and how the subsequent destruction often travels both ways). I encourage you all to give that screenplay a read if you haven’t already — it fleshes out the inside of Fargeat’s head quite refreshingly.

Now, The Brutalist. I mentioned in my Round Table response above that Brady Corbet’s talent as a filmmaker is the film’s greatest weakness, and I want to expand on that just a bit. I was very careful to include the word “likely” because at the time I wrote that response (February 17), I hadn’t actually gotten around to reading The Brutalist’s screenplay yet.

It was my assumption that the screenplay would make clear what I remember observing about the film when I saw it in cinema. Those observations are as follows, and I only softly stand by them since the film isn’t fresh in my head:

Visually and narratively, there’s nothing about The Brutalist that doesn’t outrightly work, but it’s that exact cinematic competence that allowed the film to run for three and a half hours so well.

I take no issue with the runtime — frankly, I don’t think anybody should. But the story Brady is telling here — one of what America appears to be, what America actually is, and what happens when a human merges with the specter of America — remains uneconomic. There’s a cut of this film that’s 45-60 minutes shorter, and subsequently leaves that emotional and thematic heft less diluted.

That cut isn’t necessarily better than the one we got, but thinking in terms of the screenplay — which obviously can’t channel the aforementioned cinematic competence that comfortably fills that three and a half hour runtime — I have little trouble believing that it would highlight the recklessness of Brady’s artistry here. I hope I’m wrong.

I have since read the screenplay, and I was, in fact, wrong. The script is a tight 130 pages; a far cry from the 202 pages that the film’s runtime would imply, and it quite efficiently zeroes in on the heart of The Brutalist’s story. It fills the space of that shorter cut of the film in every way anyone would need it to — it’s impressive stuff.

Could Brady’s artistry still be described as reckless in some respects? Yeah, probably, but not in any way that I feel compelled nor am probably equipped to speak on.

I will inevitably watch The Brutalist again, and if I decide I have more to say about it, those words will find their way to The Treatment. Moving on:

A Real Pain was my dark horse pick, and I selected it based on its odds of winning rather than how much it deserves the Oscar. Behind The Substance, I say Anora is the second best screenplay, but I think A Real Pain is the second most likely winner behind The Brutalist.

Let me first make clear that A Real Pain’s screenplay is genuinely excellent, even though you probably don’t need me to tell you that. It is, however, a weaker read than how it manifests in the film.4 That’s how I personally prefer to judge the screenplays — by how they’re written rather than how they’re filmed/performed, and it’s for this reason that I don’t really rate it among the other nominees.

But why is it weaker? Well, A Real Pain’s pages begin playing on the more narratively-relevant emotions way earlier, more frequently, and therefore more viscerally than the film. This dilutes the individual impact of those emotions/themes.

The film, by contrast, allows Benji and David to simply exist together and in the world, as opposed to rushing its themes/revelations to the forefront. This clues us into Benji’s character, who we quickly come to understand as a walking ball of dramatic and comedic tension.

Having established that, the film then allows the tension to ramp up from Benji’s mere presence before pulverizing us with a manic jolt. At the same time, it makes the quieter, casual layer-peels all the more significant when they happen.

The pages don’t offer that same breathing room, and those moments become less significant simply because there’s more of them. Not exorbitantly so, but worth noting nevertheless.

The pages, eager to lay the film’s deal out for us, play/riff on that deal too frequently to allow the tension to ramp up the way it does in the film. The pages are nervous about keeping its subject matter relevant, and overshares it.

The film, smartly, is more conservative about showing its hand. The film is confident enough about its subject matter to not always need to be speaking about it, and knows that if it allows it to rest, it will be powerful enough to split the Earth open when it is spoken about.

There’s another interesting element in that Jesse Eisenberg wrote the screenplay and also brought it to life on screen. A testament to his directorial ability, or notes from Emma Stone? We may never know.

As for Babygirl, I’ll save those thoughts for a proper, dedicated post that I may or may not write very soon.

Finally, this is the part where I tell you all that my “snubbed” pick was decided via coin toss. Babygirl was heads, Alex Garland’s Civil War was tails, and that’s all I’m going to say about that for now.

Best Adapted Screenplay

Contenders: A Complete Unknown, Conclave, Emilia Pérez, Nickel Boys, Sing Sing

Who Will Win: Conclave

Who Should Win: Sing Sing

Dark Horse: Emilia Pérez

Snubbed But Not Forgotten: Nosferatu

A vicious combination of Atlantic Canadian screening opportunities and streaming parameters means I won’t get to see Nickel Boys until after this piece goes live. With respect to that limitation of mine, I don’t see a world where Sing Sing shouldn’t be backed for Best Adapted Screenplay. It may be true that its competitors tango with philosophies ranging from fascinating to pressing, but it’s the pages of Sing Sing that paint the most crucial, earthly portrait; one of love and healing through the act of making art, complete with a humanistic cradling of hurt and fallibility. That’s the story the spotlight needs now more than ever. Knocking down the status quo — from either above or below — is a necessary endeavour, but we need the builders in equal measure that we need the burners, and Sing Sing’s got rivets to spare. That being said, Conclave will take it; it has all the momentum, and the mechanics of its plotting will play with voters most effectively.

At the time of me writing this post, I still don’t have the means to see Nickel Boys, and I don’t think I’m going to have them until after the Oscars at this rate. I’m sure I’ll have plenty to say on it in due time.5

Speaking of having plenty to say, I ironically don’t feel the need to say much more on Sing Sing or Conclave here. Conclave’s near-guaranteed odds of winning well and truly boil down to Academy persuasions, which I find wholly uninteresting, and I can’t really expound on my backing of Sing Sing — which I built entirely on the fact of its interest in hurt, joy, redemption, and healing — any better than I already have.

But I do want to talk about Emilia Pérez again. I’ll keep it relatively short since I’ve written about this movie twice already, but it’s nevertheless important to me that I, as a trans person, speak truth to this trans narrative whenever the forum presents itself.6

Emilia Pérez is a trans story that’s far ahead of its time, and I know this because it’s still widely misunderstood as transphobic. Many detractors like to sum up its transness with the “penis-to-vagina” song (it’s called “La vaginoplastia,” by the way), not realizing that A.) It’s a footnote in the film’s wider conversation on transness, and B.) It actually does serve a nutritious purpose in that conversation, which I’ll touch on in a minute.

In many parts of the world, transness is vilified. In other parts of the world, transness is accepted. Within a majority percentage of those other parts of the world, though, transness is only accepted when it’s invisible — when the trans person passes. When the trans person’s transness is only internal, never external. An unseen emotion, never an observable body. A secret to run away from, never a fact worthy of visibility and nurturing.

Emilia Pérez’s story indicts this. Emilia hides her past — her pre-transition life — because it is not safe for it to be known. Knowledge of her transness (i.e. her pre-transition self) would threaten her survival. And yet, she dies as a direct result of having kept her transness secret. The film ends in tragedy, but the tragedy began when she buried her pre-transition self — one of the only two corners she could have possibly backed herself into, the other being disclosing her transness, which, again, would have gotten her killed.

To contextualize this on a personal note: There was a time that I harbored a deep anger for the boy I once was, and perhaps the boy that others see in me, whether as a failure of their own good intentions or as a disrespectful, hegemonic kneejerk. But I’m older now, and it’s obvious to me how important that little boy is and always was to the life that now flourishes from within me — to deny that importance is to resign myself to a turmoil that could be aptly symbolized by the troubles and ultimate demise of one Emilia Pérez.

My life did not begin until I came out as trans, but that little boy contextualized the beginning of that life in exactly the way I needed him to. I love him for that, and if, some day, I no longer carry him on my body, I will carry him in my head, heart, and eyes, and I will do so as openly as I do now.

Transness is not allowed to exist in that way right now, and that — not the existence of trans people — is a tragedy. That’s the primary maxim of Emilia Pérez’s script, and while I mentioned in the last category that I chose the dark horse based on A Real Pain’s odds, I’m choosing Emilia Pérez as this dark horse because that maxim simply needs to be in the running.

The question: why not just strive to pass anyway? If the purpose of transition is to relieve ourselves of dysphoria, is it not pertinent for trans people to pass? To shed the pre-transition self? To firmly draw that line between pre-, mid-, and post-transition?7

It is indeed very pertinent. Now, do you have a spare $20,000+ to fork over to your friendly neighbourhood trans person so they can afford all the pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and surgical endeavors they likely need to pass? Oh, and don’t forget the time machine that will let us fast forward through the periods of waiting through the early months and years of HRT, which we can’t acquire until we’re cleared by a medical professional and a psychologist, who take a considerable amount of time and/or money to get in with, let alone be given the okay from. Make sure that time machine can move through space as well, since we’ll probably have to travel long (expensive) distances for the many surgeries, perhaps as far as Bangkok or Israel.

Welcome to the point of “La vaginoplastia.” The only widely acceptable way for transness to exist happens to involve a very expensive, dense, and time-consuming maze.

And honestly? It’s fine if you didn’t realize that. I myself didn’t clock the song’s significance on my first watch. I’m not here to point fingers; I’m here to translate art so that we can all understand each other better.

And as for Nosferatu, I’ve already said all I need to say on it for now — story and all — and you can read those thoughts here.

Bonus: Best Visual Effects

Best Visual Effects was among the five categories that I requested to write about for the Round Table (along with Best Actor,8 Best Supporting Actor,9 and the two I was ultimately assigned). I was especially passionate about one of the nominees in particular — specifically in the context of its Best Visual Effects nomination, no less — and so I want to talk about that here.

Before I do that, I want you to imagine the endorphin hit I received when I read the Round Table document and saw that Decarceration — an endless fountain of nutritious insight, as well as a writer and human that I deeply respect — also thought it pertinent to step up for Better Man.

Unlike the other films in this category, sci-fi and fantasy spectaculars that are supposed to take us to new CGI worlds, Better Man is basically one extended effect, one that is meant to do something even more challenging — it’s the creation, the integration, of a completely alien concept within a familiar, mundane world.

— Decarceration, The 2025 FilmStack Oscars Round Table

I want to expand on the sentiment here. As Decarceration alludes to here, the Best Visual Effects category is chiefly defined by the quality of immersion that the visual effects provide. The more real and evocative they look, the better your odds.

More importantly, the rest of the nominees in this category would never work with the absence of visual effects. There is no version of Dune: Part Two, Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes, Alien: Romulus, or Wicked that would be acceptable without even paltry visual effects — those effects are a mandate, not a choice.

As a Robbie Williams biopic, Better Man’s specific visual effects were not mandated, and therefore exist to serve a deeper narrative/creative purpose. It’s for that reason that I join Decarceration in backing Better Man for the “should win” of the Best Visual Effects Oscar.

Indeed, Robbie Williams’ portrayal by a CGI chimpanzee (voiced by Williams himself) creates a singular, intentional, emotional resonance that the other films’ visual effects only graze by way of their lone spectacle.

In choosing(!) to render Williams this way, Better Man paints a portrait of a man who relishes in — and is therefore condemned to — his circus chimp-like need to entertain, while simultaneously calling attention to the utterly deranged phenomenon of celebrity.

The attitudes that can be adopted on account of fame, as well as public obsession with celebrities, are both things that Better Man frames as “less-evolved” with this chimp insert.

Moreover, the chimp offers a distance from the otherwise hyperrealistic world, which allows Better Man to play with dream sequences more effectively, while also allowing for dimensions of choreography that you couldn’t access with a live-action human.

Indeed, the sheer amount of narrative and thematic heft provided by the mere existence of this left-field visual effect far outshines the novelty of riding sandworms in IMAX theaters, and that’s why Better Man should win Best Visual Effects.

Thanks again to Maria and Enrico for assembling this FilmStack Justice League and polishing up a stunning magazine to house all of our thoughts in. I once again suggest that you read it here at your earliest convenience, though I personally urge you to make time for it at your earliest inconvenience, too.

And with that, we look ahead to Sunday night.

Decarceration famously referred to us as the Film Substack Justice League. We’ve yet to discuss roles, but I do plan on calling dibs on Martian Manhunter.

Competition in general, really.

This was when I still felt compelled to treat my work like sweepingly functional fuel for the Tomatometer. You can almost feel how little I care about talking about stuff other than the themes here. I’ll probably write another piece on The Substance at some point, but this, to me, is sort of like looking at a high school graduation photo. I mean that endearingly, and I stand by what I wrote then.

Challengers is the same way, actually.

I would once again like to emphasize that it’s the trans elements I’m speaking power to exclusively. I cannot, nor should I, give you a take on the “Mexican” elements. Listen to Mexican voices for those.

To which I would also say in addition to what I’ve said below: Who decides what passing is?

Adrien Brody, but also Sebastian Stan.

Kieran Culkin, but also Jeremy Strong.

Wait but I love this picture of you!!!

Pleasure to welcome you to the league, J'onn J'onnzz. I think I'd have to be a deep-cut, like maybe Black Lightning. Green Arrow might be cool.

Anyway, yes, because I can't count at all, I actually went on for a while about "Better Man", but none of it fit the piece. I certainly think it's an effect with a purpose, rather than the other movies that feature "necessary effects." Team "Better Man".

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com